Art in the Woods

The Woods

The entrance

The steps down into the wood with the single remaining post leading to the style at the bottom.

One little area of woodland in Penwortham has been a source of growing fascination for me over the last few weeks. Accessed through a small gap in the hedge, opposite the war memorial on Penwortham hill, the steps down into it are obviously old, only a single decaying post remains of the fence that must once have bordered them. And the style at the bottom restricts no animals these days, serving only as a record of a previous enclosure. At the other side of this obstacle nature has reasserted itself – the path is barely single track and in danger of disappearing altogether. It leads through to a larger, better established footpath that connects Valley Road to the bottom of Liverpool Road.

It is the tiny area between style and footpath which has been the focus of my attention. It’s where I made piece of Land Art which reached its conclusion a couple of days ago.

I’d been growing increasingly conscious as I passed through on my daily lockdown walk of the various traces of human activity in evidence there. Like the mysterious arrows carved into just three of the trees. These little directional symbols are too substantial, too permanent, to be the left over of an afternoon treasure hunt but too few in number to offer more significant guidance. They seem to point towards the style but from where is much less obvious – the tree at the junction with the Valley Road path bears no way marks to connect with them.

Less mysterious are the initials above a heart carved into one of the other trees. These always leave me wondering if the love expressed lasted for even a fraction of the time that the letters obviously have. I suspect not but it’s nice to imagine a pensioned couple seeking out the tree to reconnect with their earliest days.

These always leave me wondering if the love expressed lasted for even a fraction of the time that the letters obviously have. I suspect not but it’s nice to imagine a pensioned couple seeking out the tree to reconnect with their earliest days.

No such speculation is needed for the unconnected initials on another trunk; they signal only ego.

There is also evidence of a more temporary nature: the occasional footprints in the muddy paths – and litter.

There wasn’t too much litter – just random spots of contrasting colour and tone. Nevertheless, someone with a different aesthetic than the one I chose to adopt on my wanderings would have been affronted by it. I chose to see it as part of the story. It mostly said children; sweet and crisp packets were the main constituents though the odd item, like a disposable coffee cup suggested an older litterer, but that particular item could just have blown in off the road.

In fact the amount of manmade litter was small, vastly outnumbered by the natural detritus of broken off twigs and branches which littered the woodland floor. How much of this is due to wind, weather and natural decay and how much to human (as in teenage) intervention remains to be seen.

The Art

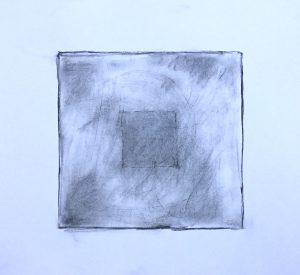

Charcoal with random scratch marks

The first square

There came a point, a few weeks into the country’s collective isolation, when being a simple observer wasn’t enough. I felt the need to interact with the place.

I decided to make something.

I gave myself certain restrictions on what I could and couldn’t do. Nothing permenant for example – no carving, cutting or breaking. I restricted myself to rearranging the materials lying loose in the area.

The form it took was easy. A couple of weeks earlier and at the time unconnected to my daily walks, I had made a drawing, the result of an experiment with some hand roughened paper and charcoal. The form of it harks back the work I did in the eighties (see History, Chapters 7 & 9). The simple fact is that I like squares and grids, particularly in relation to other, random elements. Squares offer structure and order; they also contain. In the natural chaos of that little piece of woodland the square offered the perfect foil.

Using various branches lying on the woodland floor, I constructed one. It was approximately 3 metre across and some 15 metres or more from the path. Would it be there in the morning? Only time would tell (I’d already concluded that kids, society’s beginner level vandals, were occasional visitors to the place).

Back at home I reviewed the photographs. I already knew that the piece wasn’t finished and by the following day I’d worked out how to proceed.

On the way into the wood I collected litter (including a large lump of plastic which had obviously flown off some passing vehicle and made its way through the hedge and partway down the hill). Finding the large square still in situ I constructed a smaller one inside it and placed the collected rubbish inside. The result was not a thing of beauty in the traditional sense but it was meaningful artistic statement for me and I was happy with it.

Over the following days I enjoyed walking past it and occasionally wandering over for a closer look. On one occasion I noticed an empty condom packet, alongside the other litter, inside the inner square. I hadn’t put that there. “interesting,” I thought, as we Land Artists do, and moved on

Several days later there was a different intervention. In a major act of vandalism someone had torn a substantial, living branch off the nearest tree and dropped the end of it on my structure, scattering some of the items within it. The vandalism, I should emphasise, was to the tree.

The first attack

I have mixed feelings about how I reacted to this.

I could have just left it or I could have repaired it – the damage was slight after all.

What I actually found myself doing was seeing it as a challenge. I used the torn off branch and incorporated it into the reassembled work. At one point I ended up with what looked like a stylised image of a tree, which was all right as a gentle joke but not what the original statement was supposed to be about.  So I added more wood to regain the abstraction and the symmetry.

So I added more wood to regain the abstraction and the symmetry.

The second attack

This turned out to be an act of provocation. The following day the whole structure had been destroyed, the elements cast randomly about. My reaction this time was simple acceptance. The project, I decided, had reached its conclusion. I went back with gloves and a carrier back the following day and removed all the litter, leaving nature to deal with the rest.

But the mixed feelings persist. The true Land Artist should, I feel, have left the piece after the first act of destruction, picking up the litter perhaps, but leaving what remained as it was. But there is certainly a part of me that gets pleasure from the obvious outrage that my actual actions provoked.

Not that any of it matters in the great scheme of things, of course. No art lasts for ever.

With the litter removed