Introduction

In my childhood I knew exactly what Art was. Then I went to Art College and discovered that I didn’t have a clue. In the decades that followed I spent endless hours making and thinking about Art. I made a lot of weird and wonderful stuff in that time (see History), but alongside the making, but most definitely separate from it, I sought a rational understanding of what Art really is, one that I could put into words. What follows are some of the words I’ve managed so far.

Contents

1. What is Art

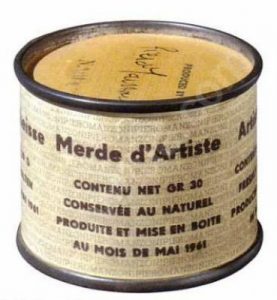

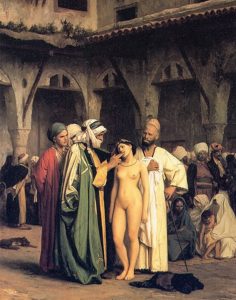

Any definition of even the visual and plastic arts alone has to cover a wide range of human activity and product. It has to cover the Mona Lisa, Picasso’s Guernica, a urinal signed with a pseudonym; a man walking across Patagonia; a tin filled with the artist’s excrement; and a lot, lot more.

Quality Control

In deciding whether something works or not the Scientists, it could be argued, have got the easier end of the deal. At least when they’ve done the measuring and calculating, and had the results checked by their peers, they know they’re right (or as near to right as Scientists allow themselves to admit to being). Artists have no such verifying structure. Art, by its very subjective nature, is a matter of opinion. Who is to say who’s right? We’ll come back to that but first we need to look how an individual Artist evaluates his own work. Without logic, laws and rules (all attempts to lay down rules in Art are immediately, successfully and rightly broken) how can an Artist have any certainty?

Fortunately the process of making Art, done properly, does offer a measure of certainty which, whilst not being as verifiable as those of the Scientists, allows the process to reach a satisfactory conclusion at least.

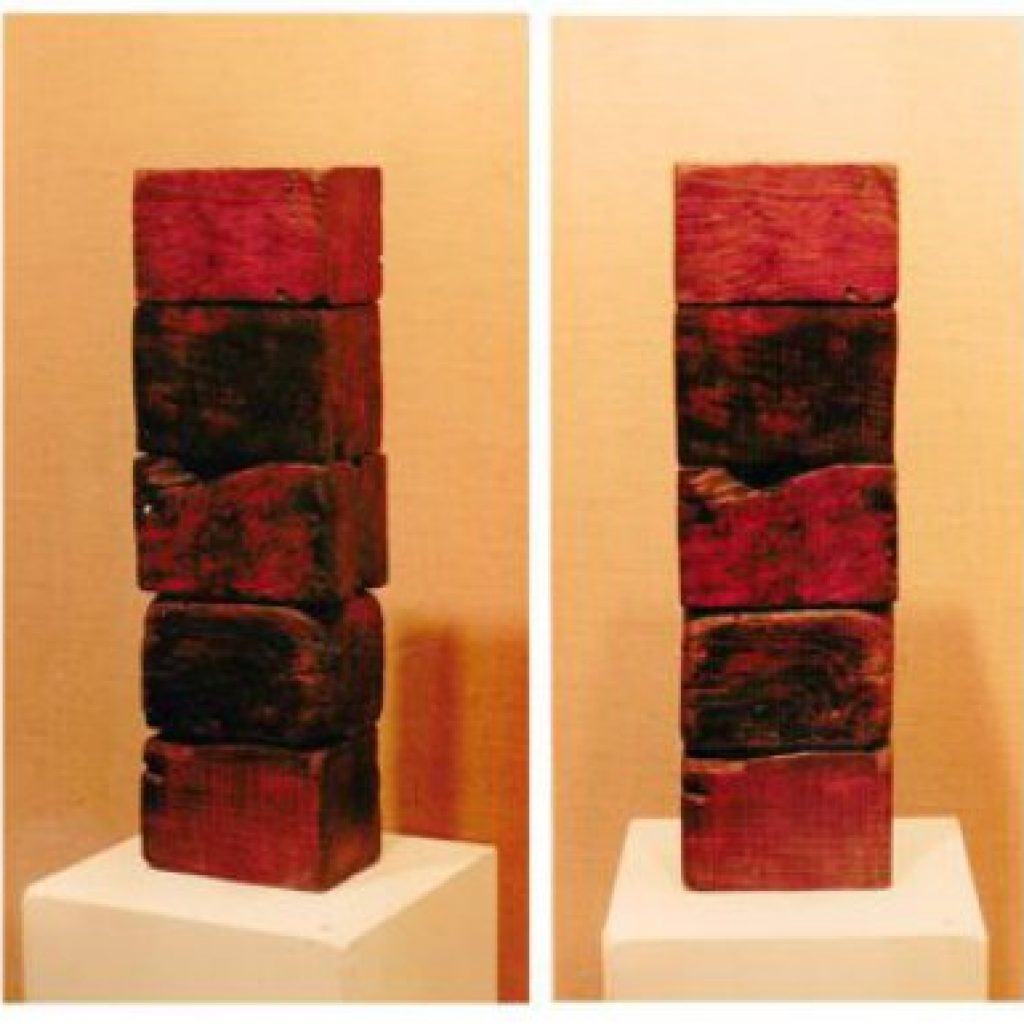

Driftwood Sculpture

A good few years ago I started messing about with lumps of industrial driftwood: lengths, blocks and flat pieces of wood that I collected from the banks of the local river. I found myself attracted to this material, some of which had been in the river for a very long time so that its regular, machine-made geometry had been compromised and corroded to varying degrees. I wanted to find a way of distilling this quality and by doing to emphasise it.

That last sentence is, I should stress, an after the fact explanation. At the time I just had some intriguing and attractive chunks of wood that I wanted to ’do something with’.

The doing involved sitting at the back of my house and arranging selected bits of this material in various combinations, looking for an assemblage that ’worked’. It was for much of the time a frustrating process as arrangement after arrangement failed to elicit a positive reaction, or did so only to finally disappoint. I would swap bits around seemingly endlessly and very occasionally cut one of the pieces in half. But there would come a point, a wonderful, blazing, gigawatt moment, when it suddenly happened. It was impossible, and unnecessary, to know why it worked. It just did.

As stated above, Art works because the discoveries of one person’s introspection strike a chord in others. The simplest example is again representational drawing. Because visual perception essentially works the same way in all people a representational drawing produced by a skilled artist draughtsman can be read by everybody, regardless of whether they can themselves draw or not. The same is true of slightly less obvious aspects of picture making. Take colour for example where the terms ’warm’ and ’cold’ are often used by Artists and designers (and people who do makeovers on TV). The warm colours are reds and oranges, the cold, blues, particularly pale blues. The reason for this is simple and obvious. In nature red and orange phenomenon are often hot – burning embers say – whereas ice, in contrast, tends towards pale blue. Reds therefore ’feel’ warm, pale blues ’cool’ or ’cold’

I’m in danger in that last example of being misleading in that it looks suspiciously like a rule. It isn’t. Colour, like all aspects of picture making, is infinitely subtle and infinitely variable and exploring it (as in exploring their own reactions to it) is one of the things that many Artists have spent a lifetime doing. My point is that what they discover should, if the viewer is open to it, be readable and possibly revelatory to that viewer – because it taps into an already existing relationship that we all have with colour.

The rider that the viewer ’be open to it’ is an important one, incidentally. If the viewer has an overly narrow expectation of what an artwork should look like they may well not be able to get from the piece what the Artist has revealed. Experience is important here. Someone who has encountered a lot, and particularly a wide range, of Art, is likely to be more tuned in to the new, the unexpected or the subtle than a viewer with more limited experience.

It becomes a question of taste. The word ‘taste’ applies to food as well as aesthetics and provides a useful analogy. Children like sweet food but as they get older and their taste gets more sophisticated they begin to prefer savoury. Some individuals go on to seek out new tastes and taste combinations and become gourmets. Art is just the same. Many people get stuck at the egg and chips stage. There’s nothing wrong with egg and chips (in taste terms that is) but it is a bit limited. With regard to Art too many, alas, never escape the sweets stage.

Having said that, taste in, and the appreciation and understanding of Art has, I perceive, expanded considerably in recent years thanks to the explosion of visual media, and the ubiquity of visual phenomenon in general, and Art in particular, on the Internet.

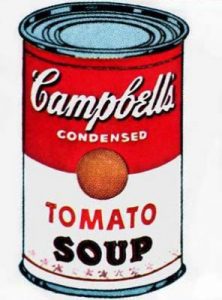

Because knowing what the artist’s intentions are and the background against which he works is useful to say the least. Showing an Andy Warhol Campbell’s Soup print to an Amazonian Indian who has never experienced any form of outside culture is unlikely to strike much of a chord. This is not to say that she wouldn’t find it interesting and intriguing but that she wouldn’t get out of it everything that Warhol put in because she hasn’t experienced the environmental stimuli that he responded to.

Of course that’s an extreme case but it serves to demonstrate how knowing the context of an Artist’s work can affect the viewer’s ability to connect with it. And it follows that those who are fully immersed in the Art world – curators of major galleries, critics and dealers, for example – are in a better position to recognise quality in new and challenging Artwork. That doesn’t mean they all can recognise quality of course – quality in Art is still a matter of judgement and there are certainly some in the ranks of those labelled as expert who seem to lack it. But all are better placed to recognise quality and hopefully a consensus arises that leans towards good collective judgement. We less well informed individuals certainly rely on them to dig out the talent and make us aware of it.

The question remains: can we get any nearer to knowing, in an explanatory way, what Quality in Art is? beauty is one word that gets banded about in relation to Art. The trouble with ’beauty’ is that it too easily gets mixed up with words like ’attractiveness’ and even ’prettiness’. Pretty is far too superficial a concept to fit the bill and most artists would be appalled to hear their work being so described. Attractive is a little better, but not much. You wouldn’t describe Duchamp’s ’Fountain’ as attractive. But it isn’t beautiful either is it? I would suggest it is. It has acquired beauty from the idea that it demonstrates and represents. Because, unlike ’attractiveness’, the word beauty’ is associated with another word – ’Truth’ – most famously by John Keats in his “Ode to a Grecian Urn”, written at about same time that Niépce was fixing the first photograph:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, —that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

As for deciding who the truly greats are, only time can really decide, enough time to allow a consensus to build which is undeniable. But time does do it. You’ll do well to find anyone, particularly an Artist, who will question Rembrandt’s greatness. The cliché that Artists are only truly appreciated after their death has substance. But is that changing? Probably not. But perhaps Artists are now appreciated in their own lifetimes over a wider audience. And the consensus does build more quickly, because modern communications and media provides us all with so much more information about them. We even get to meet them, through the window that sits in the corner of our living room and, increasingly, on our laps and in our hands. And this does, as I have suggested above help us connect with their Artwork. For me, the best Artists, seen in this way demonstrate a quality that singles them out. They have honesty, the kind of honesty that persuades them to bare their souls to the world. To discover in themselves what most of us can’t – or won’t. To uncover and reveal the truth that’s buried within us all.

The first essay concentrated on Fine Art and Pure Science. Both are activities driven by curiosity and the desire to know. Not all creative and scientific activity is so completely self-justifying or self-motivating. The introduction of Function changes things: add function and Science becomes Technology, whilst Art becomes Craft (and somewhere in the mix, Design, but we’ll come back to that). Both Technology and Craft are often seen as poor relations by the purists, to which the practitioners themselves respond with accusations of head in the cloud snobbery. Snobbery is certainly ubiquitous, not to say rampant, in the Art world, which is one of the reasons why finding a way through the minefield of opinion and prejudice is often so difficult. So, when I get to the point of suggesting, as I will, that certain products of human creativity are misnamed, or in the wrong category, my objective is not to insult but to clarify.

Hans Coper Pots – Art or Craft?

Clarification isn’t easy. Apart from anything else the dividing line between Fine Art on the one hand and Craft on the other is hardly clear cut, if it exists at all. Hans Coper ceramics, for example, whilst always having a hole in the top and thus retaining their categorisation as the work of a craftsman potter, have in many cases lost their functionality and are considered by many to be Fine Art objects.

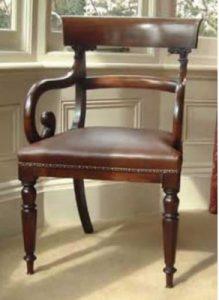

Nor is there an easily identified division between Craft and Technology. Take one common and familiar artefact – the chair. The chair is an everyday item whose functionality is unquestionable and simple. A chair can be the unique and beautiful product of an individual highly skilled craftsman; it can be the result of a technological breakthrough, possibly in the hands of an industrial designer; or it can be a cheap, simple, utilitarian construction, produced by machine.

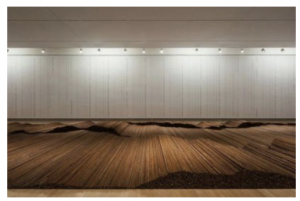

Ai Wei Wei chairs (at Yorkshire Sculpture Park)

It seems reasonable to suggest that a chair made to function as a seat is unlikely to be a work of Fine Art (though it can be used in one: see Ai Wei Wei’s ’Fairytale-1001 Chairs’ for example.)*

Whether any chair is the product of craftsmanship, however, depends on how it is made.

One vital component of a Craft, with which the word is almost synonymous, is skill. Fine Artists employ skill of course, but not quite in the same way. The Craftsman’s skill is usually honed to a specific task, or at least a limited series of tasks. And it is honed through repetition. A cabinet maker, for example, will plane, saw and chisel his way through a good few trees before reaching the level of master craftsman. And he will continue to refine and improve that small range of skills as his work continues.

The modern day Fine Artist’s approach and attitude to skill is different. She applies her skill generally and is more given to experiment than refinement.

Picasso’s ‘Goat’ – different materials used in different ways.

“I am always doing that which I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it,” is how Pablo Picasso put it.

A group of 1970s Art lovers coming to terms with Carl Andre’s ‘Equivilant VIII’.

It is, as the first essay suggested, a mistake to equate Fine Art solely with skill. It may well take skill to make good Fine Art but it is what the process and product tells us about ourselves (both as artist and viewer) and the way we connect to the world that is the point. And, as the Picasso quote suggests, the search for contemporary relevance requires the tackling of new skills, and new areas of expression. This is one of the reasons why newly created, modern day Art can be difficult to access: young artists in particular tend to work in unfamiliar media or in unfamiliar ways, causing discomfort to the uninitiated viewer.

Craft is different. Craft deals with the familiar. And whilst craftsmen certainly innovate, that innovation is gradual and in increments that allow everyone to keep pace. The craftsman made artefacts of 150 years ago are not so different from those of today. Tied to function, and a limited and familiar range of materials, Craft can produce surprises but it tends not to challenge.

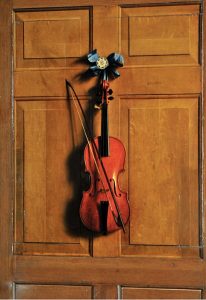

This is NOT to say that craftsmen don’t create beauty. Like artists, with whom they are seamlessly connected, by responding to their own reactions to their material and the forms they create, they produce objects and artefacts which tap into human understanding of the physical world. Craftsmen and women are in touch with the natural environments from which their media derive. Nature uses its materials efficiently in order to survive the evolutionary arms race; we humans have an innate ability to recognise the patterns and structures it creates in doing so and find them beautiful. A good craftsman taps into and echoes this. The phrase ’Less is more’, for example, is one expression which characterises this understanding. We talk about a craftsman having sympathy with his material, being in tune with it. A good craftsman allows his material to make the running – as long as it doesn’t interfere with the product’s function of course. And it is getting the balance right between these two requirements that is the craftsmen’s real skill – just as it is between an artist’s mark making and the needs of representation. Some describe a work which has this balance as having ’edge’, others as having ’tension’. Or it can simply be described as being ’right’.

Fine Art and Craft share many qualities and, as has already been stated, the boundary between them is blurred, but they are at heart different. Craftsmen tend, in their choice of materials and ways of working, to look to the past; Fine Art, at its purest and best, is anchored very firmly in the present.

Before going on to expand on that statement we need to look at the effects of Technology on Art and Craft, which brings us to Design.

When Science’s functional offshoot, Technology, began creating new materials and processes for producing the items which had previously been created by craftsmen, traditional crafts themselves went into decline. Many almost died out and maybe would have done were it not for a dedicated few, the most successful of whom were able to combine their increasing rarity with quality and sell to a relatively affluent and taste conscious minority. The majority of consumers, meanwhile, had to make do with the products of technology – cheap and plentiful and made by machine. They weren’t, in many cases ’making do’ of course; whole sections of society were actually getting products that had previously been out of their reach. In fact, as technology progressed, everybody was.

Design in action – two vacuum cleaners

And it quickly became obvious, particularly to those who were selling the stuff, that something was missing from the nakedly functional products of the technologists and engineers. Enter the Designer, someone with the ’eye’ of an Artist/Craftsman combined with the understanding and knowledge of the engineer. These were not craftsmen in the sense described above and nor are they Fine Artists. Generally they have no desire to be. Their kudos as combination artist and technologist is high enough on its own.

And it quickly became obvious, particularly to those who were selling the stuff, that something was missing from the nakedly functional products of the technologists and engineers. Enter the Designer, someone with the ’eye’ of an Artist/Craftsman combined with the understanding and knowledge of the engineer. These were not craftsmen in the sense described above and nor are they Fine Artists. Generally they have no desire to be. Their kudos as combination artist and technologist is high enough on its own.

As with Craft successful Design is all about balance, between the aesthetic and the practical. Interestingly, the great phrase which Industrial Designers use to find this balance is: ’form follows function’. This could be seen as ironic when you consider why designers were needed in the first place. In fact it’s a reminder to these creatives not to let their imaginations, their inner artist, get out of hand and to recognise that there is beauty in function, sympathetically dealt with.

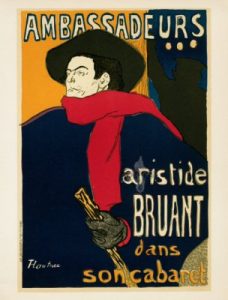

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Poster

Of course not all Designers are Industrial Designers working in 3D; we have Graphic Designers too. The transition from painter to Graphic Designer was smoother than its 3D counterpart. The technology of printing has been around for centuries and has been a medium that Fine Artists have long used to explore their relationship with the world. So it was a small step for Artists to produce images for mass production and use in commercial enterprises. The most famous example of this is probably Toulouse-Lautrec and his posters for the Moulin Rouge, but there are countless others. And they do, once again, demonstrate the lack of a clear-cut dividing line between Fine Art and its functional cousins

Nevertheless, as the technologies of mass produced imagery developed and its functional use by commerce proliferated so did the specialist Graphic Designer emerge. It is interesting that the word function has a slightly broader meaning here than its use in describing the utilitarian purpose of a chair. The function of Graphic Design is to attract and communicate but, importantly, the basic message is someone else’s. The Graphic Designer will, like both Craftsman and Artist, use introspection and rely on her understanding of, and empathy with, both her medium and the world in general, but the product is still created to fulfil a function, albeit a commercial, cognitive and/or aesthetic one, and is consequently different in nature from Fine Art.

Michelangelo – a touch of genius.

Which begs an important question: is an artist working towards a commission still a Fine Artist? Or is he a Designer/Craftsman? It depends, I would argue, on how much control he has over what he produces and how he produces it. I would argue, for example, that if a skilled painter is asked to produce a representational painting of a dog from a photograph supplied by the owner (as I was recently) the product should more properly be described as a work of Craft. This is not say that all commissioned Art should be relabelled as Craft – that would mean that Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling is not Art. If an artist is asked to fill a space in his own way, doing his own thing, it can still be a work of Art. And if he’s an artistic genius it can be an artistic masterpiece.

But it isn’t just a question of an externally directed source of content and style which can determine if a work normally described as Art should be more accurately called Craft. The nature of the process is a factor too; it can be the determining factor. There are many painters, particularly in the blunter edges of the art world, who work in ways which do have more in common with Craft than Fine Art. They work in traditional media, using well practiced techniques and oft repeated subject matter. Their next painting is as predictable as the cabinet maker’s next cabinet.

The commercial, High Street galleries are full of such work, some of it produced with almost production line skill sets and processes. But as I have stressed throughout this essay, the line between Fine Art and Craft is an unbroken one, passing through many intermediate states. There are many examples of Craftsmen whose work moves towards the Fine Art end of that line and Fine Artists heading the other way. But the distinction between the two extremes is an important one because it answers one of the recurrent arguments regarding quality in Art. What is often labelled by the Fine Art establishment as bad Art may really be good Craft. It would simplify matters if those that produce it could accept the fact and simply be proud of it as such, encouraging the Fine Art critics to do likewise..

* Making a statement like ‘a chair made to function as a seat is unlikely to be a work of Fine Art ‘ is asking for trouble. Searching for illustrations of chairs, above, I inevitably came across one that was. This is the chair from Allen Jones’ ‘Hatstand, Table and Chair’ from 1969. (Whether any body actually sat on it is another matter).

* Making a statement like ‘a chair made to function as a seat is unlikely to be a work of Fine Art ‘ is asking for trouble. Searching for illustrations of chairs, above, I inevitably came across one that was. This is the chair from Allen Jones’ ‘Hatstand, Table and Chair’ from 1969. (Whether any body actually sat on it is another matter).

As alluded to in Essay one, I was very confused at Art college (Details in my ’History’ – ’It Fits Where it Touches’). I really couldn’t understand what was going on. One of the reasons, I now know, is that in my attempts to understand I was using the wrong part of my brain. It’s a part that causes a lot of problems to the would-be and actual makers of Art, and many of those who look at it.

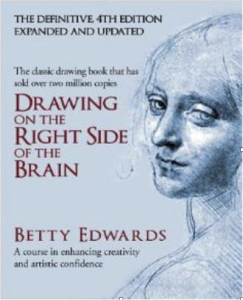

Probably the best book on learning to draw ever written.

I think it was Betty Edwards, Art Teacher and author of ’Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain’, who suggested that learning to draw is like learning to ride a bicycle. It is a good analogy. They are both intuitive activities which are difficult, if not impossible, to explain and cannot be mastered using logic, or rationality alone. Such thinking can even get in the way.

Sportsmen know this; they are only too aware of the dangers of thinking too much about what they do. They may talk strategy and analyse technique between times but when the whistle blows they rely on the non-logical side of their brains to perform at their best. In the non-reactive sports such as golf, snooker and darts – even bowling and pitching in cricket and baseball – this can be a problem, to the extent that in some sports they even have a name for it. Golfers get the ’yips’, darts players ’dartitis’. All sorts of explanations are offered for these problems but, at their heart, it seems to me, is an interfering rationality – the player’s brain ’thinking’ about what she’s doing instead of just allowing the part of the brain that’s good at it to get on and do it.

Many sportsmen go to a lot of trouble to suppress the interfering, rational sides of their brain. Their main weapon is practice, repetition of the swing or throw so may times that it becomes automatic. Even then they often resort to superstitions, wearing the special socks or touching a lucky charm before taking to the pitch or court. Anything to give the logical brain a reason to stay out of it – ’No need to think about it – I have the rabbits foot round my neck. It’s all taken care of.’ The rational brain often falls for this kind of ruse. But not in everybody.

Making Art is infinitely more complicated than any sport and the battles between rational understanding and the intuitive, non-reasoning self are consequently more problematic. In fact, when you consider that what the artist is doing is analysing his own consciousness (see essay one) the difficulties of doing it without thinking about it – in the wrong way – would seem to be impossible. And in fact, of course, it is for many people. For a significant percentage of the population even looking at certain kinds of Art without the interference of the logical self is impossible. “What’s that supposed to be?” they will cry when faced with an art work which strays from the conventionally representational. Their rational brain ’knows’ what Art is and rejects anything that doesn’t fit.

There is a solution to this problem but only if the looker, like an addicted smoker, wants to change. It involves first adopting and then keeping, an open mind (not easy to do, particularly the keeping bit), looking at lots of Art, and making choices about what you like and don’t like. It takes time, and they need to keep at it, but it is possible. Needless to say, it helps considerably if they do all this looking in the company of someone who already has the trick (as it does when learning to ride a bike).

For artists themselves the problem is considerably more difficult since it involves self-investigation – opening your mind and examining what’s there. This is only really possible at all by filtering it through a medium, be it pencil, charcoal or paint (to concentrate on the traditional media for a moment). That’s why Fine Art, as we know it today, exists.

“Painting isn’t an aesthetic operation,” said Pablo Picasso, “It’s a form of magic designed as mediator between this strange, hostile world and us.”

To perform this magic Picasso did what the sportsman does – he threw time and effort at the problem (alongside his genius level talent of course but even that only developed after thousands of hours of activity as a child and young adult). But unlike the sportsman Picasso’s ’practice’ was not a repetitive activity but an exploratory one. He drew. The sketchbook is the artist’s practice field. But whereas the golfer might make minor adjustments to his swing on the driving range, in his sketchbook the experienced artist searches and experiments. Picasso’s major works like ’Les Mademoiselle D’Avignon’ and ’Guernica’ were preceded by countless drawings and painted studies. There are, incidentally, other ways of experimentation and study, both camera and computer playing an increasing role for many these days for example, but it is surprising the extent to which drawing holds its place as the first port of call, and not just in painting – in film making, computer game creation and all kinds of craft and design, as well as in print making, sculpture and all the other media that today constitute Fine Art. (There are artists, it should be said who do their intuitive thinking and experimentation directly on the canvas – a process which usually involves much alteration and development; and, presumably, rejected failures.)

So there we have the artist, trying to commune with his inner self, feeling his way to solutions to problems which he can’t define and are difficult to put into words. And there is his rational self, worrying about its inability to understand.

Admittedly there do appear to be some artists who seem to just react intuitively to everything, for whom rational thinking doesn’t interfere much at all. Such individuals are often noticeably useless at the practicalities of life and need partners and/or agents to take care of such things.

But then we can all do with someone to lean on. In the initial stages, in simply learning to draw for example, a helping hand is certainly useful, someone to hold the saddle, to go back to our bicycles analogy. Less obviously, experienced artists benefit from a ’saddle holder’ too and such figures do feature in the history of Art, the critic, writer and Abstract Expressionist supporter Clement Greenburg being a famous example. Unfortunately, we don’t all have a Greenburg offering their support and most artists turn to their fellows to keep themselves reassured, to give them confidence that the path that their intuitive brain is taking them down is a worthwhile one to follow. It is no accident that most revolutions in Art are achieved by groups – as in the isms of 19th and 20th century Art. Just following the intuitive brain’s fancies is difficult for the rational brain to cope with, particularly when that intuition is heading off into pastures new. It needs an explanation. This explanation doesn’t have to be anything deep, like a provable fact or a great philosophical truth; nor does it, paradoxically, even have to be particularly logical. It just needs to be a reason that the rational brain can understand in the sense that it can be put into words – like the sportsman’s “I’m wearing the lucky socks today.” Of course it needs to be something which the artist can believe – wearing the lucky socks isn’t much use if you’re not superstitious – but seeing others working in a similar way, or simply having their approval, can satisfy the rational self that what the crazy, unfathomable, mysterious intuitive self is doing is acceptable.

This need for a rational prop can lead to interesting outcomes. Take for example the work of Hans Coper (mentioned in the second essay). Coper was a potter. But he was an innovative and much revered potter whose most famous works are completely non-functional. In the eyes of many, Coper’s pots are abstract sculptures. But they aren’t and Coper himself never suggested that they were. They were made mostly on the potters’ wheel and always had a hole in the top. They were pots. The interesting question is: why didn’t he move on to make purely abstract sculpture, since that is where his work seemed to be heading? My answer is that his rational brain wouldn’t let him. His rational brain could accept the reason ’pottery’ for what he was doing. Innovative pottery was acceptable because he was surrounded by innovative potters, particularly his initial mentor, Lucie Rie. He needed the pottery hook to hang his rational hat on. It needs to be said that the world is no doubt a better place for the fact that Coper stayed a potter. His works are beautiful in the extreme and have been an inspiration to countless ceramicists since.

What would have happened if Coper had made the move into purely abstract sculpture remains a mystery but for one craftsman of my acquaintance it didn’t go well. A student at teacher training college, Bill was studying to be what was then called a Creative Design teacher (previously Woodwork Metalwork). He was a superb craftsman whose sympathy with his preferred material, metal, was total. The functional objects he made in metal were extremely beautiful, a jeweller’s anvil being one piece I particularly remember – a beautiful object which was a joy to behold. Yet the course demanded that Bill make an abstract sculpture. What he made was an abomination, an insult to metal it was made from. Without the rational hook of FUNCTION his immensely talented intuitive brain couldn’t perform.

Perhaps the biggest hook of all is photographic type representation – the common convention of producing an image from a single, stationary viewpoint which corresponds, more or less accurately, or at least convincingly, with what the eye sees. No photograph needs to be involved in producing such an image (though one may); it can be just the artist and his subject, the artist and his memory, or even his imagination. It is such an ingrained part of our culture, with such a long, centuries old history that it is widely accepted as the norm, a norm reinforced by the products of the camera, which are everywhere.

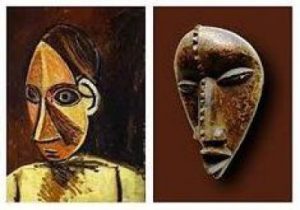

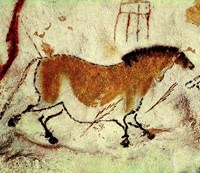

Yet looked at with an open mind there is no intrinsic reason for this domination. Plenty of civilisations have had different norms, be it African mask making, aboriginal sand pictures or even Ancient Egyptian tomb paintings (which take a multiple viewpoint approach). And the idea that such cultures were or are less able, in terms of skill and intuitive or any other kind of intelligence is long discredited. What’s more, the major artists of the last century, and more, have been pulling this representational approach apart, exploring its nature and its limits, rejecting it and subverting it, incorporating into it the artistic forms from other cultures – and so on, and so forth.

There is a group of artists, and a very large one at that, who still carry the representational flame undimmed. It’s tempting to call them leisure painters since many are just that, but others are anything but; a significant proportion are highly skilled and seriously committed artists, some trying to make a living and a reputation from what they do. What none of them are is Avante Garde, which is why I’ve given the whole group the affectionate title of the Garde Domestique, or GD for short. They are an enormous army, the GD, whose work can be seen throughout the country in tea rooms and church halls, in Open Exhibitions and Art & Craft fairs, as well as one, two man, or small group shows in galleries across the land. And here I need to come clean – I am, these days, a fully paid up member of the GD.

Although there are certainly exceptions representational image making dominates the GD, the most popular subject matter being the landscape. This is obviously no surprise; representational imagery still dominates most of the general population’s idea of what Art should be. The explorations of the cutting edge artists of the past have certainly made their inroads – Impressionism, once an outrage is now accepted completely and even abstract painting has found its way onto the walls of many a semi-detached residence; it is often a bland form of abstraction to be sure, via IKEA as likely as not, or even DIY care of a make-over TV programmes, but it breaks the representational bonds.

But for the majority of the GD creators the representational hook is where their hats reside. For those, often relatively late arrivals on the Art making scene, who are still in their formative years when it comes to making Art, producing a recognisable image is achievement enough. Other, more sophisticated practitioners are just possibly more conscious of their situation. Many like to explore the boundaries, still making images but using a greater variety of materials in a greater variety of ways. But the representational hook still dominates and it is fascinating to watch, at times, how it works.

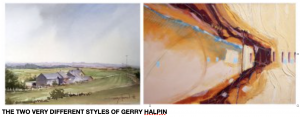

Take the case of Gerry Halpin.

Take the case of Gerry Halpin.

Google ’Gerry Halpin’ and select ’Images’ and you will see, amongst the photos of Gerry himself (and those of a few other people called Gerry) images of his paintings. These are an intriguing mixture of traditional watercolour landscapes and what seem at first glance to be abstract paintings. It’s tempting to conclude that these paintings are by more than one artist – particularly the watercolour landscapes and the abstracts. But they aren’t. Gerry, flying back from San Francisco some years ago, discovered a view of the landscape that became the basis of a whole new series of paintings, completely different from the watercolours views of the countryside he had been producing up until then. These bird’s eye view paintings of deserts, countryside and harbours (he later went up in light aircraft to do more drawings) are not only different in orientation from his previous landscapes, but dramatically different in style too. This new viewpoint, carrying less representational baggage than the traditional view, allowed Gerry’s considerable, intuitive understanding of paint, colour, composition and so forth, much freer rein. Once underway, I would guess, the paintings developed their own momentum, their own compositional, mark making and painterly demands, less restricted than those of normal representational convention. The results are certainly freer and more inventive in their use of paint and painterly effect than his more traditional products. They look abstract and are often taken as such by those who view them. They have also gained much praise and recognition in the higher reaches of the GD Art establishment. But it is important to stress that these paintings ARE still representations of a visual reality – the rational hook is still there, justifying the intuitive actions.

The relationship between each artist’s rational and intuitive thinking processes presumably varies from artist to artist and whether the rational ’explanation’ of what the intuitive brain is doing is anything more than a convenience, even an excuse, remains to be seen. Picasso certainly uses the word ’magic’ to describe what he was doing which is no difference really from the sportsman’s lucky socks.

Good Art, as I argued in the first essay, comes from the inside and it isn’t easy to get at. But then being an artist isn’t easy. The rational self needs to be kept in its place, but the tricks and strategies that artists resort to in order to keep it there remains a source of endless fascination.

Having said all that, there are areas of the Fine Art world where the rational not only intrudes but becomes part of the art work itself; when artists begin to use their skills in the use of media and the opportunity that public display of their work offers to make a rationally arrived at view more widely known. The work produced can be problematic. This is an area which I propose to deal with in the next Essay.

“I just want to make people think,” says the art student referring to his painting-with-a-message which he hopes will change the world and get him noticed. Artist Ai Weiwei does get noticed when he publishes the names of school children killed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. In fact he gets arrested and held for three months in a tiny room with two ever present, in-his-face guards. Are either of these projects Fine Art? Ai Weiwei suggests (in an interview with Tim Marlowe) that his published list of names may well not be: “I don’t think it’s Art or Not Art” is how he puts it. The art student I suspect, will insist that his painting most definitely is.

Political Art is a tricky business, and not just in repressive regimes. Making a political statement in a Western democracy is likely to result in something closer in essence to Commercial rather than Fine Art, despite the lack of monetary incentive.

Political views may arouse extreme passions and actions but they are, in a free society, the products of rational thought. Not necessarily sound logic or well informed rational thought but thought on that side of the brain. They are, in the end, externally held views, so the expressing of them is more akin to the selling of a product than the kind of exploration of self that is at the root of Fine Art.

Communist era Art. Often highly skilled but often not good Art

This is NOT to say that expressions of political views using artistic skill and knowhow cannot be important, admirable or even brilliant. Just that they are often not Fine Art as defined in the first essay. What label should be attached to them depends on the nature of the message and its form. A political message which supports the status quo, particularly a totalitarian one, is propaganda. This can be of high quality in artistic terms – Leni Riefenstahl’s ’Triumph of the Will’ being one example – but it often isn’t – see any one of the thousands of paintings and sculptures from Soviet Russia and Mao’s China. But both have more in common with Commercial Art than Fine Art because they purport to promote an idea which is not from the artist’s personal introspection

Art work which is anti establishment is more readily identified as Art. But often equally mistakenly.

Banksy

Take, for example, a work by the one of the artists of the moment – the mysterious Banksy.

The art work illustrated is obviously a political, or at least a social, commentary on the subject of immigration. It is witty and clever but if you imagine it transferred to a newspaper or, better still, the pages of a satirical magazine it would merge quite comfortably with the other witty and acerbic drawings beside it. It has all the hallmarks, in other words, of a cartoon. Which is not to denigrated it but simply to more accurately and honestly categorise it. Banksy’s work does possibly have a little more to it than its magazine equivalent. It is on a wall, in a public place and uses the details of the wall in creating the image – the crack reading as a telephone wire being the obvious feature. More importantly, context, as Duchamp pointed out in 1917, is important and the fact that these images are clandestinely produced as graffiti does at least differentiate them from their newspaper equivilants. It is worth remembering that, as stressed in essay two, it isn’t a question of either/or when it comes to definitions of Fine Art and Design in these essays but points on a continuum.

But is it possible that true Fine Art can result from or involve a political standpoint?

Ai Weiwei is obviously tired of being asked that question of himself.

The Reinforcement Rods from the schools in the Sechuan earthquake, straightened in Ai’s workshops. The names of the children who died are on the walls behind.

“People are always wondering if I am an artist or political activist or politician. Maybe I’ll just clearly tell you: Whatever I do is not art. Let’s say it is just objects or materials, movies or writing, but not art, OK?”

The Art world carries on insisting that what he produces is.

The simple fact is that Ai is an Artist but one who was born into and continues to live in a repressive regime where his honest introspections lead him into conflict with the state. His artwork ends up being political even when he may not have intended it to be. In a reversal of the famous Marshal McLuhan dictum the message starts to take over the medium.

Faced with the deaths of thousands of children it seems churlish to nit-pick about whether Ai’s response is Art or not. And given that the message is so inexorably intertwined with his daily existence, and that he is so obviously an artist of immense talent and understanding it seems reasonable to accept that it is Art of a high order.

Guernica

“But what about Guernica?” my eldest daughter now asks me in discussions on the subject.

And I begin to realise that when artists reach a high enough status in the Art community and, perhaps more importantly, the world at large, they are often inclined to use that status and their obvious communication skills to comment on matters outside their personal experience. This is almost more to do with celebrity than Art and has much in common with, say, Bob Geldorf’s Band Aid concert and Audrey Hepburn’s work as Goodwill Ambassador to UNICEF. Having said that, it is difficult to argue that Guernica is not a great work of Art and I can’t help suspecting that, once underway, the painting took over from the message. The same is no doubt true of Ai Weiwei’s work.

But none of this undermines the fact that Fine Art itself comes from the inside. It has no ’agenda’, is merely the product of personal introspection, conducted through, and made substance by, some medium or other.

So does Fine Art ever have a function? That we can deal with in the next essay.

“All art is quite useless,” said Oscar Wilde in the preface of his novel ’The Picture of Dorian Gray’.

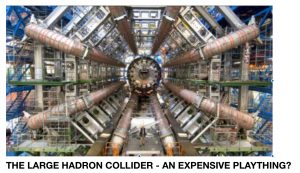

And of course he’s right. As far as Fine Artists themselves are concerned being useful isn’t the objective of Art at all, just as it isn’t the objective of Pure Science. When scientists struggled to discover the Higgs Boson, they didn’t do so in the hope that it would be useful. They did so to satisfy their curiosity, to add to their, and humanity’s, understanding of how the world works.

The world foots a hefty financial bill for this increase in knowledge and understanding – the total cost of finding the Higgs Boson, for example, has been estimated at $13.25 billion. And that, of course, is just one of the projects that scientists are engaged in. It would be nice to believe that those making the decisions about supplying this money do so purely out of the same need to know and I’m either starry-eyed or naive enough to believe that there is an element of that. But the fact is that scientific discovery does lead to useful, practical and life enhancing applications: look at where the early, curiosity driven investigations into magnetism and electricity have taken us. And it isn’t just the direct benefits. The incidental spin-offs of scientific research are also significant. The World Wide Web, created at CERN (where the Higgs was being sought) by Tim Berners-Lee is one such spin-off.

The world foots a hefty financial bill for this increase in knowledge and understanding – the total cost of finding the Higgs Boson, for example, has been estimated at $13.25 billion. And that, of course, is just one of the projects that scientists are engaged in. It would be nice to believe that those making the decisions about supplying this money do so purely out of the same need to know and I’m either starry-eyed or naive enough to believe that there is an element of that. But the fact is that scientific discovery does lead to useful, practical and life enhancing applications: look at where the early, curiosity driven investigations into magnetism and electricity have taken us. And it isn’t just the direct benefits. The incidental spin-offs of scientific research are also significant. The World Wide Web, created at CERN (where the Higgs was being sought) by Tim Berners-Lee is one such spin-off.

Having said all that it is important to stress that whilst those apportioning the funds for pure scientific research may take the practical and useful outcomes into consideration, the scientists themselves, at an operational level, most definitely do not. “There are no such things as applied sciences,” said Louis Pasteur” “only applications of science.” For the pure scientist, to contemplate practical or useful outcomes is to corrupt the process and undermine the investigator’s objectivity.

It is important to remember this as we move on to look at Fine Art.

Fine Artists, like their scientific counterparts, are seeking knowledge and understanding but in their case the search is into their own personal relationship to the world around them. And they too – the ones at the pure, Fine Art end of the spectrum – do it for the sake of doing it and not with any regard to usefulness or spin off. This, as was outlined in the first essay, was not always the case and it is interesting to note the point at which the notion of Art for Art’s Sake came to the fore. It did so in the nineteenth century when the way we humans connect to the world began to change so dramatically. The changes were many, varied and complex but it seems to me at least interesting that the notion of artistic exploration independent of function (Art for Art’s Sake) and the invention of photography happened at around the same time.

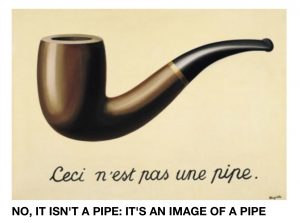

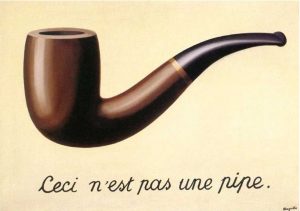

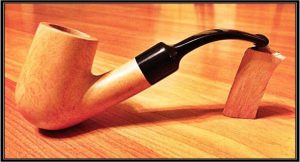

From then on, as outlined in the first essay, the way in which the world could be represented changed. And with it our notions of what is real changed. This situation was flagged by Rene Magritte in 1929 with his famous ’The Treachery of Images’.

From then on, as outlined in the first essay, the way in which the world could be represented changed. And with it our notions of what is real changed. This situation was flagged by Rene Magritte in 1929 with his famous ’The Treachery of Images’.

This simple statement highlights the tip of a very large, complex and subtle iceberg. Long before it was painted Artists were exploring the changing ways in which we perceive and represent the world. They have continued to do so since, in ways that have already been alluded to in essay one. It can be esoteric stuff of course, often little understood or appreciated by the general population. But then so are the investigations and conclusions reached at CERN.

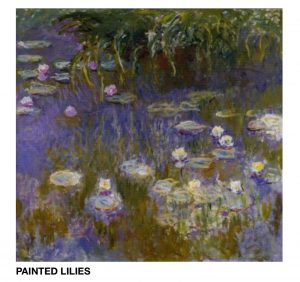

It is certainly true that the discoveries of Avant-Garde Art do filter down in time and there is spin-off aplenty. Just think of the extent to which Monet’s water lilies have permeated the worlds of Graphic Design, Textiles, and so on.

It is certainly true that the discoveries of Avant-Garde Art do filter down in time and there is spin-off aplenty. Just think of the extent to which Monet’s water lilies have permeated the worlds of Graphic Design, Textiles, and so on.

And not just the images themselves but the painterly style and way of representing nature. Yet at the time that Monet began painting in his now universally loved style his paintings were seen as incompetent, unfinished daubs by most of the art establishment of the day, and no doubt virtually every man in the street.

There is, admittedly, a difference in impact between a spin-off like the world wide web and the ubiquity of imagery on notebook covers, table mats and tea towels. That may be an unfair comparison but there is surely no doubt that on the face of it the innovations of Science lead to the greater changes to our way, and arguably quality, of life; Art, it seems, merely follows.

But this following is not without importance.

If we return to the notion that Fine Art is an exploration of the relationship between the artist and his environment – when that environment and the way we connect with it changes, then the relationship changes too and it becomes the job of the artist to explore and develop an up to date understanding of it.

What artists discover can then filter down through the artistic food chain and on to the population at large. But if, how and when it does so is difficult to assess. Take an artist duo like Christo and Jeanne-Claude who wrapped buildings and stretched curtains across valleys.

Have their projects affected the way we look at landscape and made us more conscious of how humanity has reshaped it, for the better or worse? Who can say? The artist themselves insist that the purpose of their art is simply “to create works of art for joy and beauty and to create new ways of seeing familiar landscapes”. Artists should take this view of course but surely activity like those of Christo and his partner do add to the human understanding of our ever changing world.

I’ll give the last word (almost) to the man we started with: Oscar Wilde.

In 1890, an intrigued young fan named Bernulf Clegg wrote to the author and asked him to explain the now-famous line: “All art is quite useless.” Wilde, to Bernulf’s surprise, replied:

“Art is useless because its aim is simply to create a mood. It is not meant to instruct, or to influence action in any way. It is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is sterility. If the contemplation of a work of art is followed by activity of any kind, the work is either of a very second-rate order, or the spectator has failed to realise the complete artistic impression.

A work of art is useless as a flower is useless. A flower blossoms for its own joy. We gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that is to be said about our relations to flowers. Of course man may sell the flower, and so make it useful to him, but this has nothing to do with the flower. It is not part of its essence. It is accidental. It is a misuse. All this is I fear very obscure. But the subject is a long one.” (My emphasis).

Yes the subject is a long one. And despite the understandable and necessary protestations of the Artists themselves I would argue that Fine Art does have a function in the wider world, albeit one that is difficult, if not impossible, to quantify, identify or control. Our relationship and understanding of reality is changing ever more rapidly and becoming ever more complicated. We need Artists to explore it. Whether they do, what they find or if it’s any use to the rest of us is, of course, impossible to say.

This essay was written as a reference document for the U3A Preston Philosophy Group. The subject that month was ‘The Philosophy of Art’.

Making Art always involves selection, be it choosing this mark over that mark in a drawing or which ready made objects to add to an installation. The decision may be hard or easy but explaining why you made it (and the other countless choices that precede or follow it) is often virtually impossible. “Why that line?” you may be asked. “Why there? Why that colour, that form, that particular component, that subject?” The explanation, if one is forthcoming at all, is almost always unsatisfactory to the non artist, particularly the artistically uneducated non artist.

“Because it looks (or feels) right,” is the kind of answer you get.

Some artists try and be more helpful though it often ends badly. We get treated to explanations like this genuine offering from a Cornwall based artist (it’s only a fraction of her statement):

“By exposing emotional resonances in our relationship to natural phenomena my work seeks to restore an empathetic and ecological ethic to cultural discourse.”

The art world is sadly full of such explanations; and, like this one, they’re often as useful as a message carved in soup. No, they’re worse than that, they’re misleading.

The simple fact is that aesthetic decisions are made in parts of the brain that aren’t concerned with logic, reason and everyday speech. They are consequently difficult to categorise, define or explain. When we are confronted by any aesthetic experience we can only, in the first instance, simply react – positively, negatively or not at all.

So what makes something aesthetically pleasing, what does ’aesthetically pleasing’ mean and where does it come from?

We evolved to live and survive in a complex and dangerous world and to do that we needed to understand it. In fact it was our animal ancestors that did most of the heavy lifting in this regard. They learned to recognise patterns in their environment and developed an awareness of how the world worked, an understanding of form, colour, light, structure and the way they all interact. And they made value judgements about it: what was good, useful and beneficial, what was bad, useless or even dangerous. They saw a body of water, felt good and moved towards it; smelled the scent of a predator, on the other hand, and they got a bad feeling and ran away. And hey presto, the embryo of aesthetics was born.

By the time we humans inherited our own ape adapted version of these facilities the understanding was deep and wide ranging. But now, layered over it, was a self awareness and the ability to reason.

The relationship between our conscious and unconscious understanding is the result of much scientific research but it is fairly well established that it is our unconscious understanding that we use for most of what we do. It seems that, more often than not, what we believe are our conscious decisions about the actions we take are actually mere justifications of decisions made by our unconscious. Whatever the truth is, it isn’t easy to access that unconscious; it is, by its nature, largely hidden from our conscious selves. Fine Artists are individuals who explore this hidden world (in ways that I’ve written about above). They seek its truths. And if they’re good, what they find is aesthetically pleasing, beautiful. The question is why?

We sentient creatures don’t just learn all about our environment, piece by piece, we recognise patterns, systems and rules which allow us to make predictions and handle new situations; like a child learns that adding S to a noun makes it plural. She may never have encountered a camel, but she knows that the word ’camels’ means there’s more than one. Identifying these systems and patterns makes us feel good, because they are of course useful, even vital.

One of the qualities that we unconsciously recognise in nature, for example, is efficiency. All living creatures are intrinsically efficient – they have to be to survive the evolutionary rat race. I believe we value this quality when we recognise it and, more importantly, try to emulate it. In some cases it’s obvious, like a honeycomb in a bee’s nest. These hexagonal chambers are the most efficient way the material can perform its function. And when we see it we find it beautiful.

In other situations it’s less obvious. Standing in a jungle we just see chaotic randomness. But pare away most of that chaos and hone in on an individual plant, or even some part of that plant, and we can start to gain some appreciation of how efficiently it makes use of the materials from which it is made – we can then recognise its elegance; its beauty.

This is what good Artists do. They delve into the jungle of their unconsciousness, using the tool of some medium or other, pare away the unnecessary and the unwanted in search of an essence. A truth. Beauty.

All this is complicated enough but it deepens into even greater complexity when you add our self awareness. This, in conjunction with our increased intelligence has enabled us to extend the scope of our understanding by, for example, employing metaphor.

This is most obvious, and most studied, through our use of language. One ancient example of this is the TIME IS SPACE metaphor. “Space is concretely experienced by our senses, while time is more abstract, and thus we naturally think of the latter along the lines of the former,” says language expert Stephen Pinker.

We talk of the length of a day for example. Less obvious are statements like: “summer is here”, “the weekend went by quickly”, “she has a bright future ahead of her”. (Pinker again).

This use of metaphor extends into our rational thinking. Mathematicians, those most rational of creatures, nevertheless talk of the elegance of a solution; Scientist Brian Cox, in a recent documentary, described Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity as the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen. These are aesthetic terms, subconscious values placed on conscious and rationally arrived at ideas.

Can thoughts have aesthetic qualities? Is the sentence “It’s a good idea but it doesn’t work,” just a piece of sarcasm or does it suggest that the thought did have some aesthetic value before a practical flaw was discovered?

Marcel Duchamp has described his work ’Fountain’, an upended urinal offered for exhibition in 1917, as having no aesthetic merit. Yet in December 2004 it was voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century by 500 selected British art world professionals. It is, surely, in the thought behind the work where the aesthetic content lies. What he had distilled from the jungle that is the art world at large was the simple truth that merely putting something in a gallery changes our relationship to it. And perhaps, in doing so, he introduced the notion that thoughts themselves do have aesthetic value.

Aesthetics is undoubtedly a complex, complicated and often illusive and mysterious business and it gets more complicated by the day as the world gets more complex and we humans find newer, wider and more sophisticated ways to connect with each other. But there are, I believe, core principals which govern it and it is the job of the Fine Artist to explore them.

The mistake I made, if mistake it was, was to use an image of Manzoni’s famous can of his own excrement in the blurb I handed out to the group of philosophy enthusiasts at The University of the Third Age (Preston branch). I was trying sell my ideas about Art to them, yet it became a struggle to get past this single example of mid twentieth century avant-garde Art and on to a more general discussion.

How can a can full of an artist’s bowel movement be art? they cried. Was I taking the bladder effusion? The discussion could barely get past it. And it’s come up again since. It is, I’ve concluded, time I tackled this subject head on. And to do that we need to go back a few years and look at a completely different work of art.

As the nineteenth century changed into the twentieth, strange and exotic things were happening in Art. There were all sorts of reasons for this. Representing the world had already become a complex and debatable business thanks to developments in photography and film and greater exposure to the art and artefacts from far flung cultures. By the early twentieth century views on the nature of reality itself were changing thanks to the likes of Einstein. And what’s going on inside our heads? asked Freud. Add a mechanised war that was mowing down thousands on a daily basis and it’s fair to say they were interesting times.

For the young artists of the period, the ones who weren’t actually dying in the trenches, painting pretty pictures didn’t seem to cut it and they inevitably sought new ways to explore and give expression to their own reactions to it all. The consequence was that the days when Art was easily identifiable by its physical nature – a realistic portrayal in oil paint on canvas, a figure carved in stone or cast in bronze – were waning. Art started to become stranger and for many people, confusing. I imagine this was the time when the sentence, “Well it’s very interesting but is it Art?” came into existence.

There was a lot of argument about it all and a good deal of disagreement – amongst artists themselves, those who consumed Art, those who dealt in it and those who were just interested.

At the two extremes of this debate were institutions like the French Académie des Beaux-Arts who knew a proper painting when they saw one and had rejected the Impressionists in their early days. At the other extreme, or so they thought, were groups like the Society of Independent Artists in New York. This was ’an association of American artists founded in 1916. Based on the French Société des Artistes Indépendants, the goal of the society was to hold annual exhibitions by avant-garde artists. Exhibitions were to be open to anyone who wanted to display their work, and shows were without juries or prizes.’ Art, they were saying, is what artists produce. In other words ’anything goes’. Well, not quite, it turned out.

Thanks to Marcel Duchamp.

Duchamp entered one of his readymades. But it wasn’t just any old found object. It was a urinal. It was an object designed for men to pee into. It wasn’t oriented correctly to be used that way but that’s still what it was. It was titled ’Fountain’ and the Society rejected it. Duchamp had called their bluff and called into question their supposed core belief.

Art wasn’t just what artists produce, it turned out – it’s what they, the organisers, chose to exhibit. That’s surely no different in essence from what the Académie des Beaux-Arts did. It’s just different people doing the choosing.

That urinal is now looked back on as one of the most important artworks in the twentieth century because it wasn’t just an act of protest, it said something fundamental about how we look at and react to the world. It demonstrated the importance of context, both in terms of what we know about an object and where we see it. Our reaction and relationship to things depends not only on what we see but the circumstance in which we encounter them. This is a fundamental fact about our relationship with everything and Duchamp’s fountain demonstrated it in a single and simple act (and it did it, let’s remember, in 1917).

It’s a fact that how we look at Art generally is affected by where we see it. Much as we might like to think otherwise, we react to a painting hanging on the wall of friend’s semi-detached differently to one we encounter in a prestigious gallery. And when a Japanese student puts his spectacles against the wall of a modern art gallery it should come as no surprise that people look at them differently than they would had they encountered them on a table in the cafe. Context matters. And it pervades everything, not just art. This is the great truth which Duchamps fountain revealed.

Before moving on from number ones to number twos I’d like to conduct a thought experiment.

Imagine I offer you two drawings, one of which you can keep. These pieces of paper are completely identical with the single exception that one has a small letter ’a’ on the back in the left bottom corner and the other a ’b’. ’a’ is a genuine Leonardo drawing and ’b’ a completely identical and indistinguishable copy. Which will you choose?

It seems safe to assume – to me certainly – that everybody will choose ’a’, the real Leonardo drawing if only because you could sell it for a lot more than the copy. But let’s not muddy the waters with money, let’s change the experiment so that you only get to hold the real Leonardo drawing for a few moments before handing it back. I’m still sure that virtually everybody would choose ’a’. The opportunity of holding an object touched by the great da Vinci is just too seductive pass up.

But what has that to do with the quality of the drawing? Surely, as far as the work of art is concerned, given that the two pieces of paper are identical, the experience of them should be the same. But it isn’t. And the reason is in our heads. Duchamp’s Fountain had already touched on the notion that what we know about things effects how we react to them, and as the fifties turned into the sixties the young Italian artist, Piero Manzoni started to explore this phenomenon further by selling balloons. You could blow them up yourself or he would blow them up – you just had to pay more for the second option. The balloons looked identical – were identical to all intents and purposes – the difference was inside the balloon, but more importantly it was in the owner’s head. Manzoni had demonstrated a truth which I tried to demonstrate fairly clumsily with my ’thought experiment’. He did it simply and more directly, using a balloon.

And now to the can. Manzoni was a big fan of Duchamp’s – as so many artists were (and still are) – and it may well have been the scatological component of ’Fountain’ that inspired the Italian to up the ante. He filled some cans with his own excrement. It is the same statement as the balloons but with extra power. These are mundane, supermarket shelf objects, but they’re so much more than that because of what we believe they contain. That sets up a conflict which the balloons didn’t. The can has been produced by an artist and as such has worth. So for that reason you might want it. But what it contains is abhorrent, so you don’t want it. But hang on, it’s in a sealed can. It isn’t going to smell or anything. Yes but we KNOW what’s in there. Yuk! But remember it is the artist’s own yuk so that makes it special….

And so on.

It works for me.

So that is my own take on what Manzoni’s cans are ’about’. It is, it might be argued, a restricted view. But it is in the nature of Art that the meaning as well as the beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Because of the way that Art is produced – intuitively, the artists dragging ideas from deep within themselves – even they aren’t always aware, on a conscious level, of all that they have uncovered.

It can take others to see it. For art critic Stephen Bury for example these cans are “a joke, a parody of the art market, and a critique of consumerism and the waste it generates.”

And it is true that Manzoni’s cans were produced in 1961 when the consumer age was getting up a head of steam. And is interesting that Warhol’s much more famous cans, of soup, were produced the following year. I’m not suggesting any kind of collusion or even cross fertilisation, just that cans embodied something about the time for both artists.

Manzoni’s cans don’t fetch what Warhol’s do – £97,000 as opposed to $11.7 million – and in non monetary terms they’re held in nowhere near the esteem and reverence that Duchamp’s Fountain is.

But they are Art, they’re not a con and although I’ve no doubt there was an element of humour in their conception they aren’t just a joke either.

I’m glad that the Tate has one

I’m all for cutting edge artists working in up to date media, in fact that’s really where the cutting edge should be in my opinion. But there are times when video art passes me by, and last week, at the Venice Biennale, I was reminded of the fact. This is not, I should stress, because it’s bad art. It’s more complicated than that.

The Venice Biennale is lavishly dotted with video installations in both its main venues, the Giardini and the Arsenale, and for me they’re a problem.

There are 29 national pavilions in the Giardini alone, each featuring the work of one or more artists. There is also the large Central Pavilion with 35 more art filled rooms. It takes some getting round in a single day and it’s inevitable that you’re going to miss stuff and fail to give some of the exhibits the time that they deserve. And I’m only talking about the static, material stuff, the exhibits made from paint, stone, plastic or bits of old aeroplane. But there is a sort of remedy in the case of these unmoving, concrete offerings. It’s one which most visitors employ – take photographs. You can then peruse the images later and check out the artist’s work in other ways and at other times.

But even without these aide de memoire it takes only moments to decide which individual pieces or artist you might want to give more of your limited time to. This is not, admittedly, an ideal way to look at art but given the alternative of travelling to a whole load of other countries or waiting until each artist exhibits their work in yours it’s a necessary compromise.

Videos are a problem though. Videos require time to even partially evaluate and in many cases it is only by watching the whole thing that the artwork reveals itself. Yet often there’s no indication of how long the video is and when it starts. These are important pieces of information when time is at a premium. I once visited an exhibition of video installations at our local gallery. It took four or five visits before I chanced on the beginning of one of the longer films. This isn’t an option when you’re only in town for a few days and there’s so much else to see. I do understand, incidentally, that some of the videos are on a loop and have no beginning or end. But many do, and knowing their duration and starting times would be handy.

The other problem is comfort.

The convention seems to be to screen videos in empty, curtained off spaces furnished, at best, with a small plain box with room for no more than five or six people to sit on.

Why are they so uncomfortable? If I’m going to spend time watching Bruce Nauman walk a line, or the comings and goings from an artist’s window in East Germany why do I have to sit on a hard, backless box to do it? (Neither of these are videos from this year’s Biennale, incidentally, but stuff I’ve seen in the past, as are the ones I’m about to mention).

I am, of course, aware that some video artists do think quite seriously about the way their work is presented and how it reacts with the space it inhabits. In fact they can be tailored to do just that; it can be part of the experience, part of the work’s raison d’être.

An installation by Yang Zhenzhong called ’Let’s Puff’ is a simple example. It consists of three screens two of which are on opposing walls and interact as the actions of an actor on one screen – blowing air – appears to affect the scene on the other screen. It sounds trivial but it works beautifully. And there is no need or desire to sit, when standing you feel somehow more involved and included.

A more traditionally formatted video installation is Christian Marclay’s highly praised ‘The Clock’. Exhibited in Venice in 2011 and Tate Modern some months ago it was lavishly seated in both venues. But then it is 24 hours long – not that anybody’s ever sat through it in one sitting.

What is interesting is the fact that this movie, an unusual one admittedly, is both exhibited and marketed as a work of art. Five copies were sold, there are two artists proofs and it can only be played in one venue at a time. You won’t be seeing it at the pictures or on telly any time soon. But when it is exhibited the venue is transformed into a temporary cinema – it certainly was at the Tate for example. Of course it’s both popular and highly regarded enough to justify such a transformation. Not so some lesser and shorter works, because the simple fact is that videos don’t easily fit into the art gallery format.

Art galleries are designed to display paintings and sculpture. It’s cinemas that are designed to show film. So why don’t video artist show their work in cinemas, or on Netflix or Amazon Prime? The simple answer is: because they’re artists.

As Marcel Duchamp demonstrated in 1917 with ’Fountain’, Art is often defined by the location where it’s encountered. Because of the historical nature of Art – paintings, drawings, sculpture etc – the gallery has traditionally been that location. It has become the place where an artwork’s status as art is acknowledged. What’s more, the level of that status is decided, to quite a considerable degree, by the status of the gallery. So if you’re a video artist and want to be recognised as an artist, you need your video to be exhibited in one of these temples of aesthetic excellence and not the local Vue or Odeon.

That’s just the way it is, but it’s far from perfect.

I’ve watched a video displayed on a wall, whilst standing and wearing headphones. I’ve watched one seated on one of three, small stools, each no bigger than, and resembling, an upturned bucket. I can understand that lack of space might explain the former but the latter – the upturned buckets? I actually suspect that it’s a kind of aesthetic snobbery. A dozen or so canteen style chairs would spoil the look and lower the tone whilst better looking seating isn’t affordable. But it’s more than that. It’s almost as if we should expect a little discomfort in pursuit of our cultural improvement – like kneeling on a hard floor in church. I think it’s supposed to be good for our aesthetic souls. Well I’m sorry. I am willing to suffer for my art, but that’s my art, the stuff that I’m making, not other people’s. I’m eager to be moved, exhilarated, enlightened and improved by their work but I’d like to do it in comfort please.

It’s all a bit frustrating, particularly that, given the technology available today, we could theoretically be watching these videos in the comfort of our own homes, streamed via the ever present internet.

It isn’t going to happen though. Artists are not going to exchange the status enhancing prestige of the galleries and major exhibition venues for the anonymous infinity of the World Wide Web. Nor will the Netflix/Amazon Prime option cut the mustard either – they’re far too down market.

What could work might be some kind of licensing arrangement, whereby a gallery visit gets you a temporary pass code to watch the video on the internet later. For more complex installations we could use Virtual Reality. Having said that, I tried a bit of Virtual Reality last week in the Arsenale. The headset didn’t work.

The Tate Bricks

This essay was written in response to a non artist friend’s request to ‘explain’ the famous Tate Bricks. It turned into a whirlwind tour of what Art is and how it works. So hold on to your hats. (Having said that, if you’ve read any of my other opinionated rants, above and elsewhere on this site, at least some of it will be repetition.)

Carl André, the artist who ’made’ the bricks (Equivalent VIII in 1966) was/is a Minimalist.

So what is Minimalism, apart from an attitude to Interior Design which demands clean lines, no ornaments and definitely no clutter? To explain what Minimalism is in Art it might be easiest to explore my own Minimalist artistic tendencies which have, at times, been quite severe. In a recent essay I wrote about the process by which I used to make Art (and still do occasionally).

There are five stages:

1. Having something catch my attention by simply looking at the world.

2. Wonder what it was about the phenomenon that is so attractive, attracting or interesting.

3. Explore it through drawing, making and thinking – often a great deal of first and third particularly.

4. Make choices throughout this process on the basis of ‘like’ and ‘don’t like’.

5. Arrive at a Eureka! moment when some defining essence emerges – in the form of an actual artwork.

You’ll notice I’ve picked out the words defining essence. You could use other expressions like ‘underlying structure’, ‘core value’ or ‘nub’. Scientists tend to end up after their investigations with a law, usually represented by a simple equation; like Boy’s Law (PV=k), or Einstein’s famous E=mc2. That’s their defining essence.

However, unlike Scientists who try to separate themselves from what they are studying Fine Artists (the Fine bit is important) do the opposite. In fact they not only include themselves, they are, I suggest, the subject of their study – they analyse their own reactions to the world. And they do this mostly using some kind of medium which helps them to externalise their investigations both mentally and physically. These media used to be limited to paint, stone, clay and wood but with the advent of photography and many other technologies the list of media grew. These days anything can be a medium, literally anything.

Now the thing about media is that they are not passive. They not only give, they make demands. And they always have done, particularly for artists working in 3D. Michaelangelo, for example, famously said: “Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” That’s a statement that needs explanation and it’s probably easier to do so using the medium of wood. Wood has a grain and if you work against it your sculpture will be weak whereas if you work with it the sculpture will be stronger and will almost certainly look better. You’ve got to respect the medium and every medium is different.

3D artists can often feel that the medium itself is calling the shots. If they’re sensitive to such things – and a good artist should be – they feel that the medium ’wants’ to do certain things. In Michangelo’s day this simply meant his being sympathetic, of finding the balance between the demands of the medium and the demands of the subject matter.

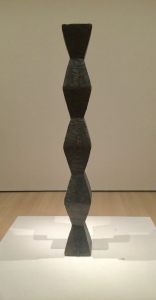

In the last couple of centuries, as photography took over the representative role this relationship changed. Artist working 2D, for example, started to examine the more fundamental components of picture making, exploring the marks, shapes and colours alone. In sculpture where the influence of the medium was greater the kinds of abstract forms which resulted became increasingly determined by the medium used. An early example of this was the work of Constantin Brâncuși, a ground breaking sculptor and hero of Carl André’s.

‘Endless Column 1’ by Brancusi. Carved out a solid piece of oak.

‘The Kiss’ by Brancusi. Given the extent that the stone block determines the form the sculpture is surprisingly sexy.