Contents

Chapter 2 – Recovery – ( Space(s) – Arrows – Pipes – Roads and Houses )

Chapter 3 – Chorley College – ( Photography and Action Man – Girl – Cutouts )

First, the title. It is, quite simply, a sentence my mother used to utter. She was a tailoress and spent her life making men’s suits. She would knock off a pair of trousers in the morning then cut out and baste up a jacket in the afternoon. She was proud of her skills and very critical of the products of other people’s. ‘It fits where it touches!’ was her greatest insult. It often came shortly after ‘They are nobody,’ which alluded to the suit owner’s lack of pedigree. She claimed to be of the landed gentry, because her grandparents had been, or so she said. She certainly wasn’t when she had me and my brother. Not only was she a poorly paid seamstress but her husband, my father, worked in a cotton bleaching mill where he had reached the heady level of foreman before dying suddenly of a heart attack when I was fifteen.

First, the title. It is, quite simply, a sentence my mother used to utter. She was a tailoress and spent her life making men’s suits. She would knock off a pair of trousers in the morning then cut out and baste up a jacket in the afternoon. She was proud of her skills and very critical of the products of other people’s. ‘It fits where it touches!’ was her greatest insult. It often came shortly after ‘They are nobody,’ which alluded to the suit owner’s lack of pedigree. She claimed to be of the landed gentry, because her grandparents had been, or so she said. She certainly wasn’t when she had me and my brother. Not only was she a poorly paid seamstress but her husband, my father, worked in a cotton bleaching mill where he had reached the heady level of foreman before dying suddenly of a heart attack when I was fifteen.

Actually, come to think of it, what my mother meant by ‘It fits where it touches!’ – i.e. it doesn’t fit at all – is not what I mean in the title. For me this little sentence just suggests the randomness that I see when I look back at my artistic life (calling it a career would be more than misleading). From the relative objectivity that time provides it is fascinating to note the degree to which circumstances decided what I produced. This is as it should be, of course. If art’s about anything it’s about reacting to whatever’s around you.

Of course the artist’s environment and external stimulus are only part of the equation, the other being the artist himself – or herself. What follows is a description of my responses, what they were responses to and how they developed. I’ve tried to make it interesting. Of course, whether it is depends to some extent on the artwork itself. By this, I don’t mean whether it’s any good or not. Trying to decide where any work fits into the great artistic scheme of things in terms of quality is, I increasingly find, an impossible and often distracting activity. These days I just try and react to whatever I see as best I can and leave it at that. Deciding whether your own past work is any good is definitely impossible. This is not to say you shouldn’t aim for excellence when you’re making the stuff, merely that, once it’s in the past, it just is what it is and that’s all.

There is another way in which the title is appropriate. My memory fits where it touches too. My recollection of things on the distant past is frighteningly incomplete. What’s more it seems almost randomly so. Why should I remember a piece of sculpture I made in my first year in the Sculpture Department of Manchester Art College well enough to reconstruct it on paper yet have forgotten others that I produced much later? Only the discovery of some contemporary photographs reminded me of some of the latter, others have almost certainly gone for good.

And talking of the photographic record: that too leaves a lot to be desired. Some of the gaps are down to simple bad luck but other problems are self inflicted. I may have copped out of deciding how good my old art work is but I can’t escape the fact that I was, and still am, a useless photographer

Chapter 1 – Art College

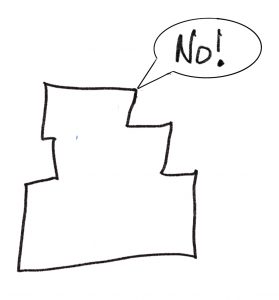

A Negative Shape?

“You’re not looking at the negative shapes,” said the lecturer accusingly. He was a small bearded man and looking back over the fifty years which separate now from then, not all that much older than I was. Having said that he was a lecturer, and lecturers by definition, knew everything. They knew what a negative shape was, for one thing.

I didn’t. A shape was just a shape as far as I could see, in this case the shape of the pile of easels we’d been set to draw. A shape could be too fat, too big or just wrong – but negative? How could it be negative? Even in Maths, where negatives lurked around every confusing corner, the term had never been applied to shapes, not in my five years at grammar school at any rate. Shapes in maths had names and classifications, and they usually had letters attached to their corners for use in theorems. But negative?

Worse still, it seemed to be just me who was ignorant. The beard had been talking to me, but had said it loud enough for everyone else to hear. No one had asked what a negative shape was. They obviously knew.

Well, I wasn’t showing my ignorance, not in my second day at Manchester Regional College of Art. Not likely. I kept quiet. Needless to say, I couldn’t do anything else to the drawing. I might make the negative shapes even worse. I just sat and fiddled with it a bit.

And it had all started so well.

On the first day we’d been put in temporary groups and this nice lady lecturer (the lady bit making her unique in the establishment as far as I can remember) had us drawing potted plants. What’s more she had held up mine and said, “Now that’s what I’m looking for!”

It actually felt quite normal to be singled out for special praise. It had been happening since I was nine, when my primary school teacher had announced that he’d found an artist. Being another educational god, not to mention something of an artist himself, I took to his praise like a duck takes to small fish. I worked very hard from then on to get more of it. I don’t know whether it was natural talent or just the hours I put in but I actually got quite good at drawing. What’s more, the results began to garner praise from more than just my teachers. Friends and family alike were impressed by my developing skills. They made me special. It quickly became something I couldn’t give up.

Somehow I passed my eleven plus (the somehow being a private tutor paid for by my far from wealthy, working class parents) and went to grammar school, a very good grammar school as it happened. Unfortunately, in the mid fifties, this meant treating their pupils as information receptacles, the filling of which was achieved by writing stuff on a blackboard and having said pupils copy it down. I didn’t take well to this. Usually my mind wandered off to somewhere a lot more exotic, usually to the accompaniment of some above average doodles.

Of course it was different in the Art department. In there I was a star. When the school got a new young head of Art in my fourth year I became the star. I also had my eyes opened to a thing or two.

It seems difficult to believe it now but, with the sixties still in the future, Impressionism was seen as a bit rubbish in the cotton towns of Lancashire. Not as rubbish as Picasso, admittedly (he was quite obviously a lunatic conman, even the newspapers said so) but nowhere near as good as the likes of Constable and those other honest British artists who painted nice things that looked real. But given a combination of adolescent rebelliousness, the new art teacher (who’s name, appropriately, was Young) and something in the British air that would eventually culminate in the Swinging Sixties, I was soon taking the view that Constable was a little bit last season.

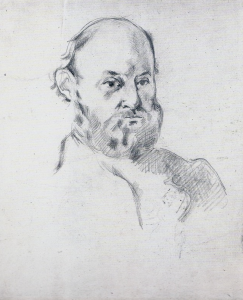

It would be nice to announce that I now caught a glimpse of the contemporary art world, said ‘Yes, that’s for me!’ and dived in with gusto. Alas no. I merely managed to crawl forward a few decades through the nineteenth century. Presumably with the help of Mr. Young I discovered Cézanne.

It would be nice to announce that I now caught a glimpse of the contemporary art world, said ‘Yes, that’s for me!’ and dived in with gusto. Alas no. I merely managed to crawl forward a few decades through the nineteenth century. Presumably with the help of Mr. Young I discovered Cézanne.

It wasn’t the greatest leap forward in the history of art but then I was only fifteen; I wasn’t ready for Abstract Expressionism, even if I’d seen any examples of it.

But, looking back, Cézanne was a significant discovery. What I liked about him was the way he constructed his images from visible strokes. I started constructing my drawings out of short straight marks. In addition to accuracy they now had style. I had discovered ‘mark making’ though the term wouldn’t be in use in educational circles for a several decades. Unfortunately the discovery didn’t survive my first few days at art college. And ironically, one of the nails in its coffin was provided by a man who was, I now assume, trying to promote it.

Lecturers in those first few days seemed to change daily though that’s probably a trick of memory rather than an accurate recollection. This one was bald and wore a suit (which wasn’t that odd in an art college in nineteen sixty – give it three or four years and it would be start to become odd). Bald, suited man took us into a nearby park, pointed down at the uncut grass and said he wanted us to draw it. ‘But I don’t want to see any blades of grass,’ he announced pointedly. Of course I know now what he meant and perhaps I should have known then given my Cézanne inspired drawing style. He meant that we should make marks to represent the grass, its flowing swirls and spiky clumps. The trouble was he didn’t say that – he preferred enigmatic to explanatory, leaving me and most of my fellows more than a little confused. (The exception was this mad girl who nobody really talked to. She was off on her own behaving madly as usual, rotating on one leg in a mad little dance. Of course she wasn’t being mad at all. She was creating patterns in the grass which she would then translate into a bold and vibrant drawing in charcoal. Of course we didn’t look at what she was doing. She was mad after all).

He didn’t even explain when we questioned him later, after we’d all scribbled a bit and given up. He just said he ‘wanted to destroy our preconceptions’. He didn’t even show us the mad girl’s drawing. The truth was, I suspect, that he didn’t really want us to understand. He’s either dead now or very, very old. Serves him right.

It is, of course, unfair to single out one bald man in a suit as responsible for my confusion. The whole place was confusing. Everywhere you looked there were paintings, drawings and prints that just looked like inept, meaningless scribbles to me. Yet they were praised. Cézanne was last season as well, it seemed. This was the latest fashion and it looked bloody awful to me.

I didn’t fret about all this. The young are used to not understanding things, it goes with the territory. I somehow believed that if I hung around long enough there would come a point when a light would go on and I’d suddenly understand. And I wasn’t on my own. Other people were confused too. One or two of them even admitted it.

But for me the lack of understanding took away my ability to work. How could I draw, paint or make anything when I hadn’t the slightest idea whether my output was any good or not? Even praise proved destructive.

‘Excellent,’ one of the lecturer gods said about a life drawing I had almost completed in his weekly lesson. ‘Pity you’re not using a softer pencil.’ He didn’t say why it was excellent, why it was it any better than the drawings I’d done in previous weeks, or why I should use a softer pencil. All of which left me with nowhere to go. I certainly couldn’t touch my excellent drawing. I’d probably ruin it.

I was apparently capable of excellence but didn’t know what excellence was, a belief that was reinforced when the same lecturer praised the work of other people which looked rubbish to me (like the mad girl’s). I’m not saying it was rubbish; it was probably just too sophisticated for my severely uneducated palate. Whatever the truth, the result was that an artistic stasis descended on me.

It might have helped if the lecturers had explained a bit more. But they didn’t. In retrospect this isn’t all that surprising. These mostly young lecturers claimed neither expertise nor interest in education. They were artists, and artists don’t explain. This is not, as many then believe, because they’re trying to con everybody. It’s more that explanation requires analysis, of a kind which runs counter to the whole process of making art. Analysis is dangerous. Art is done by ‘feel’ and feel is a delicate creature. Letting logic near it can kill it.

Of course they couldn’t explain this either.

As for the learning, I think that was supposed to take place by osmosis.

Given my by then total lack of confidence and consequent inability to do anything it is something of a miracle that I survived the next two years. At the time, but not for much longer, a two year, mixed syllabus of drawing, painting, sculpture and craft ended in the Intermediate examination. I remember virtually nothing about this examination, apart from having, on the advice of my craft lecturer, to abandon the pots I’d spent most of the allotted two weeks making and attempt the other of the two options. I designed, threw, turned, fired and glazed a tea caddy in three days (proving, if nothing, else that I did, even then, have the capacity to work, given a clear target and enough pressure). Despite this, no one was more surprised than I when I actually passed. God knows how I did it. Perhaps I produced another brilliant drawing.

It was time to specialise.

What to specialise in was a no-brainer, though an older interpretation of this expression might be more appropriate than its actual modern one. Despite the fact that I was in a state of artistic calcification borne of confusion and lack of understanding with regard to painting in particular, I applied to join the Painting Department.

It is perhaps worth pointing out that Manchester Art College was an exciting place at this time, full of exciting and charismatic people. And the most charismatic of all were the painters. I wanted to be one of them. Surely the penny would drop eventually if I just stayed around for long enough. And who knows, the Painting Department lecturers might make it happen – they were the real experts after all. They weren’t, it turned out, prepared to make the effort. They took one look at my pathetic excuse for a folder and pointed their painterly thumbs at the floor. ‘No thank you. We were all at college with David Hockney (most of them had been, at Bradford); we can afford to be choosy; we only take people who’ve actually done something over the last two years. Thanks for coming. Don’t forget your folder, you might want to put something in it sometime.’

Fortunately, the Sculpture Department weren’t so choosy.

There was a reason why the Sculpture Department wasn’t choosy – it was in almost as bad a state as my folder. It was situated in the cellars and walking into it was, at first glance, like walking back into he 19th century. My first memory of it was of several almost finished, life size, clay life figures being worked on by students who looked a bit old fashioned themselves – they looked more artisan than artist.

There didn’t otherwise seem to be a lot going on. The head of department, we soon learned, was a raving alcoholic whom nobody had seen for months and almost certainly wasn’t coming back. In the meantime the department was being run by two relatively older men called Norman Aspinall and Bill Bailey. Norman and Bill were facing something of a crisis.

Manchester Regional College of Art was about to be transformed into Manchester College of Art and Design. And this was to be no mere cosmetic change. It was part of a transformation of the whole of higher education in Art. The National Diploma in Design (NDD) which I was about to embark on, was being replaced by the Diploma in Art and Design (DipAD). There were all sorts of dramatic differences between the two courses, many of which were to affect me personally, but the most immediate was that NDD was a two year mixed course followed by two years specialisation whereas DipAD was one year mixed followed by threeyears specialisation. This meant that the first of the DipAD students were starting their sculpture course on the same day that we were. Poor Aspinall and Bailey found them selves with three groups, one in it’s final NDD year, facing an exam in six months time, one embarking on an exciting, spanking new course (which, incidentally, most of the smaller Art Colleges in the country weren’t allowed to do), and us. Guess which group got sent to the zoo for a week to draw the animals. And guess which group were stuck in a converted corridor when they got back and left to their own devises for the first term.

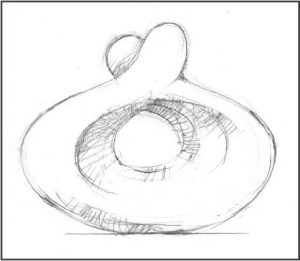

I actually enjoyed those few weeks. We bonded, we forgotten few. What’s more I was able to get on with some work without any danger of a lecturer coming in and saying something confusing about it. I was actually producing an abstract piece in plaster when one did. It had started off as an image of two grappling wrestlers (a starting point provided by Mr. Aspinall I think) and ended up, after a good deal of simplification through drawing, as a kind of Barbara Hepworth-like egg shape.

The next three years were some of the most exciting and frustrating in my life. Exciting because there was an artistic revolution going on around me and frustrating because I didn’t have the confidence to join in. I’ve long been fascinated by the human ability to hold two completely contradictory views at the same time, but that’s exactly what I managed to do during that period. I was able to believe myself to be an artist working at the cutting edge of the modern art world whilst being so confused and lacking in confidence that I did virtually nothing in the form of artwork at all. I spent most days in the pub where I got very good indeed at darts and table football.

To be fair, I did actually make some sculpture and some of it did, I’m sure, have merit. But none of it ever went anywhere. And my lecturers couldn’t do anything about it. I don’t know to what extent there were aware of this – Henslar once told me that I only talked sense when I was drunk. This meant, in fact that I must have made sense quite often, but never unfortunately in circumstances, or for long enough, to be any use. And what I did make was in the exciting new materials of welded metal and plastics that the DipAD students were using so that, when I came to the old fashioned, Victorian, academic NDD examination (for which you could work in any medium you liked as long as it was white plaster, and no bigger than two foot six) I struggled. And failed. They let me do another year during which I did more stuff in a variety of media, and failed again.

I went back to Chorley, where I’d come from; an ex art student with no qualifications to speak of.

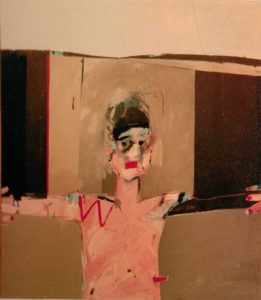

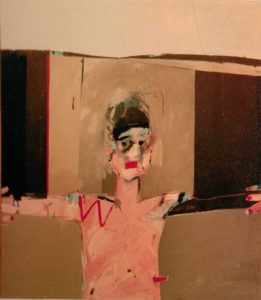

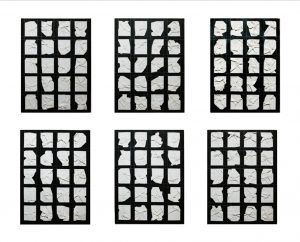

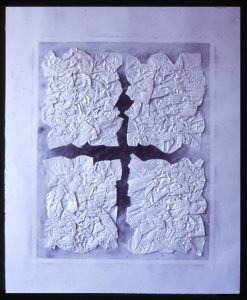

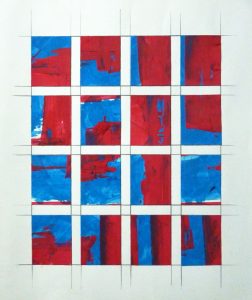

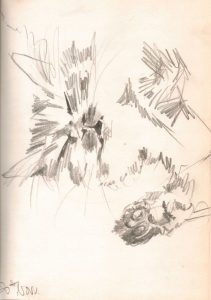

Below are some recently discovered images of ‘work’ I did during those uncomfortable art college years. What is interesting is that although I could remember ‘The Wrestlers’ sculpture (above) well enough to reconstruct it, I had actually forgotten these pieces until I rediscovered the images.

Back To Contents.

Chapter 2 – Recovery

So there I was, out in he world with a big F stamped on my forehead. Two F’s really, having failed the NDD exam twice.

I carried on trying to make art for a little while. Pure momentum I suppose. None of it survives in any form, even memory. I do have a vague recollection of messing about with toy soldiers and epoxy resin but the most solid recollection is of that familiar and uncomfortable feeling of not really knowing what I was doing.

I even gave up on art for a while. I sought out other intellectual stimulus in the local library, going through the non fiction shelves, almost at random.

I learned quite a lot, about a lot of things, from Ethology to Egyptology, Ancient History to Astronomy. I particularly liked books about Science. In fact I’m tempted to suggest that I discovered Popular Science before it became truly popular. (Why, oh why, I wondered, had I not paid more attention at school – and then I discovered my old History textbook from school – History being another favourite from the library shelves – and discovered that it was just as boring and impossible to read as I’d found it at fifteen.) Interestingly, one of the subjects I didn’t read about was Art.

It wasn’t all intellectual stimulation though; I did get myself a job as a bus conductor, in order to feed, clothe and house the wife and child (soon to be two) that I had managed to acquire. This, the bus conducting, turned out to be a significant move in terms of my artistic development.

Most of the buses by then were, in the vernacular of the trade, ’front loaders’ meaning that the doors were no longer at the back. Coupled with the fact that we conductors spent only a relatively tiny part of our day collecting fares this meant that I spent much of my eight hour shifts looking at the world through a giant, moving, picture window.

I found the view stimulating. What’s more, I began to respond to that stimulation by making things.

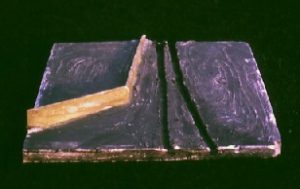

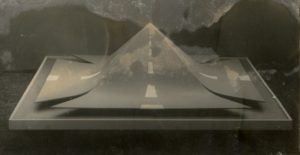

One piece which survives, in photographic form at least, is a 15″ or so square of plaster with a piece of cardboard embedded in it and a couple of widening grooves created by dragging two fingers through the wet plaster. These two features created an artificial perspective. It was inspired by the sight of a farmer’s tractor tracks disappearing over a hill alongside a dry stone wall.

I didn’t think much of it at the time and certainly didn’t show it to anyone (not that I had anyone of any significance to show it to). I find myself reacting to it quite fondly now. I like its simplicity and its immediacy as well as the simple statement it attempts to make about the way we visually connect with and represent the world.

I didn’t think much of it at the time and certainly didn’t show it to anyone (not that I had anyone of any significance to show it to). I find myself reacting to it quite fondly now. I like its simplicity and its immediacy as well as the simple statement it attempts to make about the way we visually connect with and represent the world.

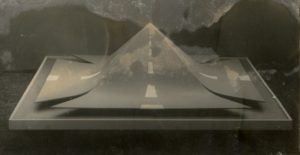

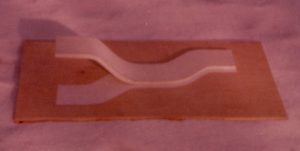

Another surviving image is of a curious little construction. It was inspired, I think, by bus borne visits to the local ordinance factory, a truly enormous site dotted with camouflaged buildings with mysterious, concealed doorways that you could never quite see into. I have less affection for this piece though it has some significance in the light of what came later.

I started, in my workaday travels, to become fascinated by street signs. There was something about these simple graphic representations of what lay ahead that I found intriguing. But why, or how they could be incorporated into some kind of art work, I had no idea. So, I decided to do what several of my lecturers had always advised – advice I had rarely taken whilst under their tutelage – and did some drawing. It was probably the most important decision of that era of my artistic life – perhaps not just that era.

I used layout pads for the main part – those books of flimsy paper used by graphic designers. I used them because they were cheap. And that allowed me to scribble and sketch without worrying about the price of the paper and, therefore, without being intimidated by it.

And, as I travelled around, gazing through the front window of my bus, I drew in my head as well.

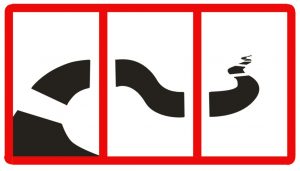

What emerged from all this drawing, looking, and pondering was the realisation that these signs were only really interesting in situ. It was their context which gave them their appeal. I became fascinated by the way in which the road down which we travelled was represented, its configuration predicted, by these simple diagrams. Crossroad, bendy roads, T-junctions and roundabouts were all preceded by little black on white, red bordered, variously shaped pictures.

This flimsy A1 sheet was typical of the many I produced during that period, along with more worked up drawings on better quality paper (See Illustrations below).

The drawing bottom left became the chosen version

And I ended up with a street sign of my own. The object itself is long gone along with any direct photographs of it, but it is fairly easy to reconstruct from the drawings.

Computer mock up of ‘Road Sign’ painting.

It was painted, using gloss paint, on hardboard, with a recessed support on the back meaning it stood proud of the wall. Unlike the real street signs it combined the bird’s eye view schematic of the signs with conventional perspective, using the broken white line in negative to marry the two together. It was, in other words, two pictorial conventions combined in a single image.

This piece was, actually, an enormous breakthrough. I understood it in a way which I had never done any previous creations. And importantly that understanding was the result of a lengthy period of investigative drawing – both actually and mentally. The question of whether it was any good or not was, in a way, irrelevant. It was the Eureka moment made real. Of course I thought it was good. No artist, be they Sunday painter, Royal Academician or Turner Prize hopeful, can struggle to a personally successful artistic conclusion without believing the product has merit.

Below are just a few of the many, many drawings, mostly on cheap graphics paper.

Back To Contents.

Space(s)

In the meantime, the buses, with me chatting to the driver and watching the world go by, continued to crisscross the county. And what my gaze began to increasing fall upon was the then (and still) ubiquitous JCB diggers.

I found these yellow mechanical dinosaurs fascinating. And they offered more sculptural possibilities than the street signs. But it was by no means obvious what that sculptural form would be.

>It was here that the experience of my struggles with the street signs came to the fore. That had taught me of the (personal) need to search for the essence of my attraction to an object or physical phenomenon. And it had also given me the method of finding it – drawing, drawing, and more drawing. (See below)

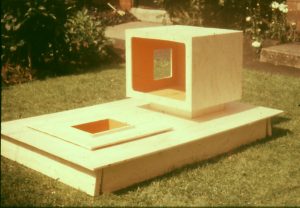

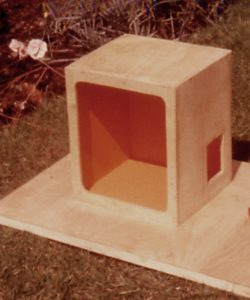

What started to emerge is not what you might expect. I don’t know whether it was the effects of all that time in the artistic sharp end at Manchester (confusing though they were), the result of the drunken conversations with my tutors maybe, or just me, but I rejected the obvious sculptural attractions of these mechanical beasts – their power and dinosaur like menace. For whatever reason the results of my manic drawing sessions and bus borne ponderings was an increasing interest, not in the giant metallic, hydraulic driven machine itself but the connection it created, between the man in his little glass sided box, to the hole he was creating in the ground. It was the relationship of those two spaces that I found most intriguing, so much so that, by the time I finally committed myself to an actual structure the digger had disappeared altogether.

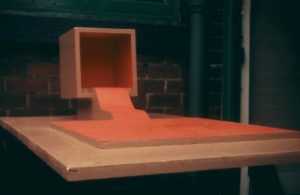

In fact, in the second piece, one of the spaces had disappeared too as I became simply interested in the relationship between internal and external space.

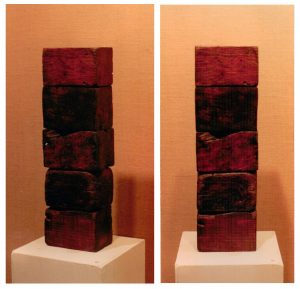

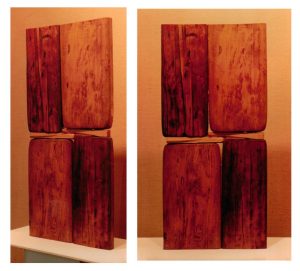

This was exotic stuff. Here, on my own, in the little town of Chorley, in the mid to late sixties, without another artist in sight I was discovering a kind of minimalism. Of course I didn’t know I was and if a real minimalist had wandered by I’m not sure how I would have reacted – probably badly. But one didn’t and I carried on in total ignorance of such things. I was conscious that the people who were around me – my long suffering, non artist wife and our equally non art savvy friends – were completely mystified by the wooden constructions I was busily producing (“And you say it started off as a JCB digger…?”). It is perhaps because of this that, in some of the photographs I’ve added arrows, and in one a small cut-out silhouette of a figure. It was, I think, an attempt to make them more accessible, as in “imagine wandering through this space,” or “think of the movements through or past it.”

Looking back I wish, in pure artistic terms, that I’d had the understanding and/or confidence to make them even simpler.

In one final, finished structure the internal space spilled out to become a flattened two dimensional area. This was a relationship I would explore more fully, and a lot less minimally in years to come.

Not that it mattered in the larger scheme of things because I made no attempt to exhibit them anywhere, in fact some of them weren’t even finished or properly stuck together; I merely photographed them (very badly more often than not) and then pulled them apart in order to re-use the wood. My sole goal was to understand, along with some vague, naïve and completely unrealistic notion that, once I’d gained that understanding, I could become one of the art college lecturer gods.

Arrows

In the meantime I continued to draw. The surviving drawings show a continuing interest in roads and their signs and symbols and it was one of those symbols that began to dominate: the arrow.

The humble arrow symbol is a powerful pictorial device. Consisting, at its simplest, of no more than three lines, fattened out to a triangle and a rectangle to make a shape, the arrow exerts an irresistible response from us. Our attention is directed by it. We may not wish to follow the orders it gives us but we can’t help registering its message.

It’s easy to write that now. At the time I just responded to the stimulus as every self respecting artist should. I drew, on paper and in my head, searching for a form or configuration that would crystallise the way I felt about this potent little visual artefact. I came up with the construction which I’ll call ‘3 Arrows’ (none of my work ever had titles at the time)

Degraded photograph of actual piece.

I have enormous affection for this little relief construction (it’s about 60 cms wide). It decorated the chimney breast in our little terraced house for several years.

I later produced a second arrow construction. This consisted a very large black arrow pointing down to a box containing other, smaller arrows cut out of wood and painted red. This piece graced the bar of Chorley Teacher Training College for a few weeks after one of their students saw it at my house. The other students used to play with the bright red, wooden arrows from the box apparently, creating routes hither and thither – from where to what and indicating what I never knew, but was delighted that they did.

I think this piece came quite a bit later than the ‘Three Arrows’ piece though it attempts to do the same thing. I felt then that it was more successful, and still do. In a way it was unfinished business. The ‘Three Arrows’ piece almost worked; this one did.

It was exhibited in Chorley College canteen, before I was a student there, thanks to a someone from the college who saw it at our house.

Pipes

I had, by this time, moved from bus conducting to working in the office of a large, local rubber factory, a company that made everything in rubber from conveyor belts to hose pipes, tubing to O rings, floor tiles to twenty-thousand-volt-proof switchboard matting. Not that any of these objects or materials entered into my artistic consciousness for the simple reason that I didn’t really have any contact with them. I worked in the sales office, pushing paper for the most part. However, this is not to say that the factory environment didn’t provide any stimulus. I did walk around the ramshackle group of buildings that comprised the factory on a regular basis, to ask this foreman or that what had happened to the order for fifty thousand grommets, which I’d passed to him four months ago. But it wasn’t the grommets that intrigued me (he hadn’t got around to manufacturing those anyway) but the maze of pipes which ran here, there and everywhere else.

And they were everywhere. They emerged from the walls at seemingly random points, joined several of their fellows to hug the brickwork for one yard or twenty, perhaps pass across a gap to another building, and disappear into some other wall, or at another point in the same wall. I found them fascinating.

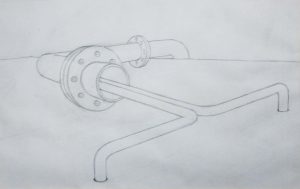

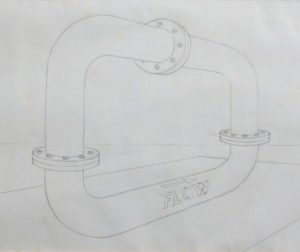

So, back at home, I drew pipes.

Typically by now it wasn’t the intricate patterns and complex weaving that I found really interesting – exciting and beautiful though these were. What emerged, through the now familiar process of paring away the clutter, was something else. And it was encapsulated in the final drawing in the sequence; three simple sections, connected to nothing but each other with the inevitable arrow and the word FLOW painted on it.

What was really fascinating about these long cylindrical conduits was their mystery. To the uninformed observer that I was, there was no indication as to what they were conveying, from where, to where or in which direction.

What was really fascinating about these long cylindrical conduits was their mystery. To the uninformed observer that I was, there was no indication as to what they were conveying, from where, to where or in which direction.

I never made this sculpture, or any of the other pipe configurations I’d committed to paper. I had neither the expertise nor the money to do so. And, if truth be told I was growing disillusioned with making things that either took up space I didn’t have, or were pulled apart or discarded once photographed. I also hated the job. God how I hated that job.

It was time to look elsewhere.

I had always resisted the idea of secondary school teaching for the rather grandiose reason that it would ruin me as an artist. It’s actually almost embarrassing to write that sentence, given the abject failure of my attempts to become an artist at art college. And there is, I suppose, an irony in the fact that I did begin to contemplate it once I had finally started to find my artistic feet.

In truth I wasn’t really committing myself to a life in teaching when I endeavoured to join the local college of education. What I was really hoping for was three years of being an artist in a place with lots of facilities and people of like mind. The fact that I might end up with a teaching qualification was by the by.

Having said all that, getting myself accepted and supported for three years was no simple, and definitely no easy, matter. It took well over a year of letter writing, waiting in outer offices and meeting a lot of rejection. But the thought of spending another forty years in the offices of that rubber factory focussed my mind considerably. I had nowhere else to go so I went on pushing. And I did eventually succeed.

But before that, in between all the writing and pushing, I continued to produce art work.

Back To Contents.

Roads and Houses

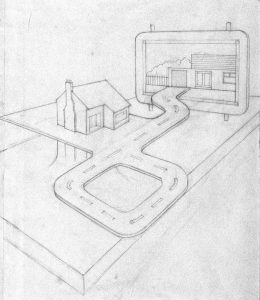

I may have left the mobile viewing platform of the bus but I still made a twenty-five minute journey to work and back each day. The roads continued to fascinate but were now joined by another common feature of the urban landscape; the house.

In fact it was one house in particular which caught my attention first. It was small and square, isolated from it’s neighbours and surrounded by a relatively well kept lawn, broken only by a path to the front door.

This path also circumnavigated the house separating lawn from the house in a metre wide strip.

Needless to say I drew houses. A selection can be seen below.

What emerged, after a good deal of exploration, were a series of sculptural landscapes containing houses and roads. In these the latter floated free above the well anchored house. Once again I failed to turn the drawings into three dimensional structures, until the final one, the drawing for which, more or less coincided with my entry into Chorley College of Education.

Back To Contents.

Chapter 3 – Chorley College

Luther Kenworthy sounds like a cross between a modern movie villain and the dupe in some Elizabethan conspiracy. He was actually the principle of Chorley College of Education in the nineteen seventies. I never met or even saw him during my three years there but was more than conscious of his effect on the institution he ran.

Luther believed in freedom.

Nothing was compulsory at Chorley College of Education; it was a case of ‘anything goes.’ And it’s fair to say that an awful lot did. It was a mature student college and almost all of the students were on a second educational chance. They consequently tended to take a positive attitude to Luther’s freedom. Many played hard – some very hard indeed – but most worked hard too.

Those who had chosen Art as their main subject brought a wide range of skills and experience with them. There were a small number who could boast at least a taste of art college education, others for whom Art had been no more than their favourite subject at secondary school. The mix was further enriched by the fact that all three years worked together in a single group. This was possible because there wasn’t anything resembling an actual course – just space, facilities and time, a combination much appreciated by most, though not all, the students.

There was a tutor, called Edmund. Edmond was a fantasist, one of those individuals who had told and embroidered his crop of personal anecdotes so many times that they had lost all connection with any form of reality. Many involved the physically impossible, like his claim to have spent a whole night hanging by his hands from a stage set – he had been painting late into the evening and his ladder had slipped from beneath him. All these anecdotes were quickly told to new students by older ones, meaning that, by the time you got them from the horse’s mouth it became difficult to keep a straight face.

My own attitude to Edmund was ambivalent anyway. If I’d reached one conclusion in the preceding six years, it was the importance of making my own artistic decisions. It wasn’t that I was still wary of lecturers or tutors, or even dismissive of them, simply that I saw myself as better off without them. Looking back at myself and the work I produced during that period it seems obvious now that I was ready for some expert mentoring. Unfortunately, Edmund wasn’t the one to provide it. Apart from his tenuous grasp on reality he was also something of an artistic traditionalist. The only piece of artwork I saw him produce during my three years at Chorley College was a very accomplished watercolour landscape, produced in situ on one of our Mains Week sketching trips to Cornwall.

My memory of what kind of artwork my fellow students produced in that first year is once again woefully incomplete but suggests that it too tended towards the traditional. Landscape and still life predominated with occasional forays by some into abstraction.

But whatever the subject and style, those who could get on with it did, and Edmund was happy to let them.

I got on with making my Extended Suburban Landscape.

Looking back I find myself wondering what my fellow students made of this strange construction. For many, it couldn’t have fitted in with what they understood to be art. But it did for others, particularly once I’d explained how it encapsulated my feelings about suburban landscape and combined those with my recurrent fascination with various two dimensional representations of a three dimensional reality. (I was learning to talk a good artwork by the stage). It also helped that I could draw a bit too.

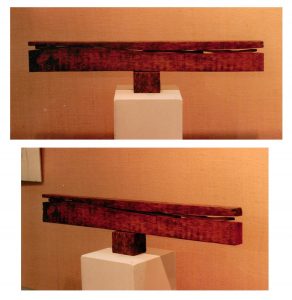

I carried on working – in between Education seminars, Secondary Science sessions (my second subject) and various other bits and pieces. I made the ‘4 Roads’ sculpture

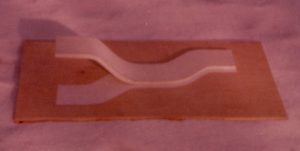

followed by a small piece I’ll call ‘Curved Form with Shape’- I don’t remember its contemporary title – it could have been ‘Curved Form with Shape’.

This turned out to be the last of the landscape based sculptures.

Photography (and Action Man)

I now discovered photography – and my five year old son got an Action Man for his birthday. I think the photography came first.

The Art Department had a dark room. Not only that, it had a seemingly inexhaustible supply of materials. Which is just as well since, incompetent photographer that I’ve already admitted to being, I ruined more paper than I usefully developed. This technical incompetence was to bear its own fruit later but for the time being it was just part of the learning process. Of course, incompetence apart, the big question was, what to photograph? It was somewhere around this point, I would guess, that Action Man entered the picture.

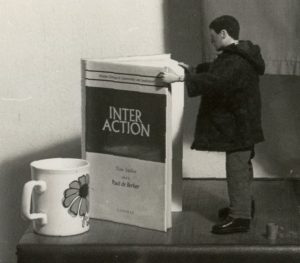

Surrounded as I was by students busily attempting to represent reality in pencil and paint, some with freedom and style, others with varying levels of difficulty, my own fascination with representations of, or substitutes for, the real – begun with that first traffic sign painting – resurfaced. Or, to put it another way, and one which better accords with my actual, if moth eaten memory, I began to play with Action Man, with my camera and with the exciting facility of the college dark room.

‘Play’ it might have been but it raised some interesting questions. Action Man was real, wasn’t he? Ok, not ‘he’ but ‘it’ – Action Man was a real doll. But it was still a representation. But what of? A human being, a person, an idea? A photograph was definitely a representation but was it more real than a drawing? Was it more real than the doll? Where did a photograph of the doll fit in? And what about scale?

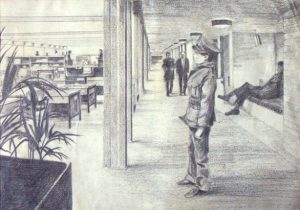

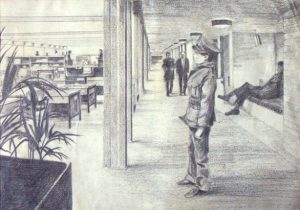

I did make one attempt to search for some insight through drawing, by superimposing an image of Action Man on an image of an office.

It didn’t do very much, and not only because Action Man is out of scale with the environment – he hasn’t been scaled up enough.

It didn’t do very much, and not only because Action Man is out of scale with the environment – he hasn’t been scaled up enough.

Drawing obviously wasn’t the right exploratory tool – it took up too much time given the level of detailed realism involved. The camera and the darkroom took over the role of the sketchbook.

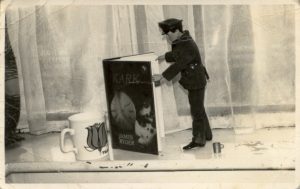

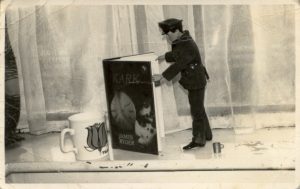

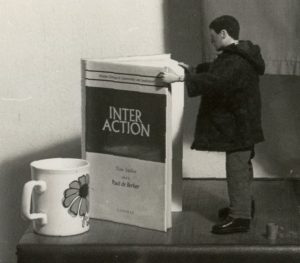

I took some photographs of the little doll connecting with various ‘real’ objects and printed them off life size. I assembled and photographed one little tableaux several times.

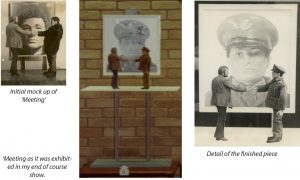

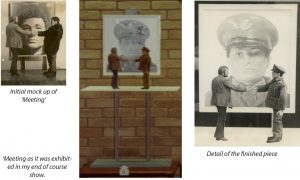

I wanted, though, to introduce some additional two dimensional elements into the mix. I first took a photograph of his head and blew that up to human size. And then I got someone to take some photographs of me, blew those up to Action Man size, stuck them on some stiff cardboard and cut them out. And then, of course, I continued to play. The eventual result was ‘Meeting’

We had enjoyed our brief relationship, Action man and I. (That he enjoyed it is without doubt – the whole point of dolls is that they think, act and feel how you want them to act, think and feel). But now, my five year old son, Rupert, decided that it was time for Action Man to concentrate on what he was designed for, i.e. killing imaginary foes and causing general mayhem. In other words, Rue wanted his birthday present back.

We had enjoyed our brief relationship, Action man and I. (That he enjoyed it is without doubt – the whole point of dolls is that they think, act and feel how you want them to act, think and feel). But now, my five year old son, Rupert, decided that it was time for Action Man to concentrate on what he was designed for, i.e. killing imaginary foes and causing general mayhem. In other words, Rue wanted his birthday present back.

It was time to move on anyway. Deciding where to go was easy. I was now hooked on photography.

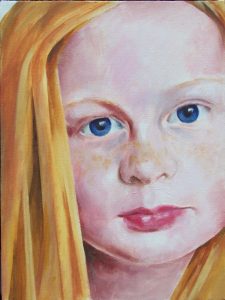

Girl

This is not to say I became obsessed with f stops and exposure times, or had a desire to emulate Cartier Bresson or Robert Capa (my recent dalliance with a soldier notwithstanding). I brought a sculptor’s eye to the subject, or my sculptor’s eye at any rate. Sounds crazy, I know, but it’s true.

One of the ideas that the Manchester Art College sculpture department had engraved onto my psyche was that the form of a sculpture is (or should be) as influenced by the material it’s made of as it is buy its subject, if not more so. Michaelangelo gave this notion a boost long ago, of course, when he said that “Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” In the early seventies the American Marshall McLuhan (who’s first name, I have only recently discovered, was Herbert) took this idea to a new extreme by suggesting that the medium was the message, not least in his best selling book The Medium is the Message: An Inventory of Effects (1967).

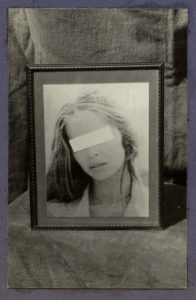

Fired up by these notions I didn’t take photographs of things, people or views, I took photographs of photographs. And then I went into the college darkroom and used my far from expert technical skills to develop the results.

The subjects of these experiments where usually images from magazines. The effects of translating them into simple black and white snapshots were fascinating. An image of an anonymous model in a magazine was public property, no more than an attractive clothes horse; in snapshot form it became the image of an acquaintance – or so it felt. I decided to choose a single image and explore further.

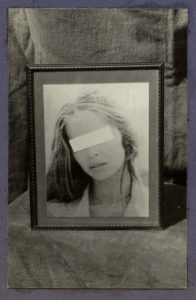

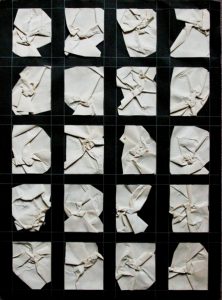

It was here that my poor darkroom skills became temporarily advantageous. Mistiming the development time changed the image again, failure to focus the enlarger properly and a different feel resulted. The product of these accidents and subsequent explorations was a series of images and objects which, in my end of course show, I simply described as ‘Girl’.

I saw the artwork then as the full collection of experiments, albeit with some pieces picked out for special treatment. But then it was an end of course show, laid out for assessment, sketch books and other preparatory material included. If one piece was the final, stand alone, artwork it was ‘Family Portrait – Identity Withheld’ This is a modern title – it didn’t have one at the time.

I saw the artwork then as the full collection of experiments, albeit with some pieces picked out for special treatment. But then it was an end of course show, laid out for assessment, sketch books and other preparatory material included. If one piece was the final, stand alone, artwork it was ‘Family Portrait – Identity Withheld’ This is a modern title – it didn’t have one at the time.

The original piece as exhibited at the time.

where it lives now, in a modern frame on the wall of our box room.

It didn’t do very much, and not only because Action Man is out of scale with the environment – he hasn’t been scaled up enough.

It didn’t do very much, and not only because Action Man is out of scale with the environment – he hasn’t been scaled up enough.

We had enjoyed our brief relationship, Action man and I. (That he enjoyed it is without doubt – the whole point of dolls is that they think, act and feel how you want them to act, think and feel). But now, my five year old son, Rupert, decided that it was time for Action Man to concentrate on what he was designed for, i.e. killing imaginary foes and causing general mayhem. In other words, Rue wanted his birthday present back.

We had enjoyed our brief relationship, Action man and I. (That he enjoyed it is without doubt – the whole point of dolls is that they think, act and feel how you want them to act, think and feel). But now, my five year old son, Rupert, decided that it was time for Action Man to concentrate on what he was designed for, i.e. killing imaginary foes and causing general mayhem. In other words, Rue wanted his birthday present back. I saw the artwork then as the full collection of experiments, albeit with some pieces picked out for special treatment. But then it was an end of course show, laid out for assessment, sketch books and other preparatory material included. If one piece was the final, stand alone, artwork it was ‘Family Portrait – Identity Withheld’ This is a modern title – it didn’t have one at the time.

I saw the artwork then as the full collection of experiments, albeit with some pieces picked out for special treatment. But then it was an end of course show, laid out for assessment, sketch books and other preparatory material included. If one piece was the final, stand alone, artwork it was ‘Family Portrait – Identity Withheld’ This is a modern title – it didn’t have one at the time.

The original piece as exhibited at the time.

where it lives now, in a modern frame on the wall of our box room.

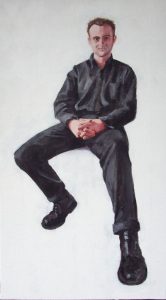

Cutout Figures

I was now at the end of my second year. My third began with a move to a brand, spanking new, custom built college on the edge of town. At least we thought it was custom built until we discovered that the Art Department had a low black ceiling and Chemistry steel sinks (just watch that nitric acid burn straight through). The latter didn’t effect me because I’d finished with second subject Science at the end of year two.

So there I was, in the new, spacious but low ceiling Art Department, facing a final exhibition in a few months time. I don’t know if this was a factor in my decision to go large and dramatic but this is what I did. I decided to see what would happen if I scaled up an image of someone to real person size and get rid of the background, thus reducing as many of the differences as possible between the two dimensional image and its subject.

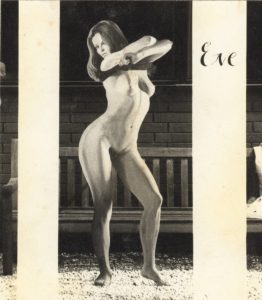

It’s tempting to suggest that it was modesty that stopped me scaling myself up. In fact I wanted something more potent. I came up with the idea of a naked female – as artists, particularly male artists, have tended to do since the dawn of time. And, for reasons of cost, copyright and the unavailability of a suitably willing and attractive model, I was going to have to paint her, from an existing photograph. The source was obvious. If ever there was a group of images which acted as substitutes for the real thing it was the naked young ladies in girlie mags.

The research for this project wasn’t I admit, particularly onerous, once I’d overcome the excruciating embarrassment of acquiring the necessary materials. The image I needed, though, had to fulfil fairly exact parameters. It had to be of a complete, standing figure, photographed from a low to mid level viewpoint with a longish lens. I found an image which fit these criteria and set about reproducing it life size in paint.

I soon encountered difficulties, largely emanating from the fact that I hadn’t painted in a photographic style since I was sixteen.

The fragments of recollection that I insist on referring to as my memory has me painting an oversize hand for some reason (possibly a precursor to the figure) and failing miserably. I do remember painting a single finger or thumb after that in order to relearn the technique.

Eventually I developed the confidence to paint the first pinup girl (1st image below).

I had reached the conclusion that this image was a bit too powerful in its enticing sexual provocation (I was at a teacher training college after all) but probably, more importantly, she wasn’t as well painted as I would have liked. So I painted Eve.

She was slightly more subtle as a sexual provocateur – though not subtle enough, it later turned out .

I was never completely happy in giving her a name, incidentally, since it threatened to upset the balance between object/image and person that the piece was supposed to be about. It had the danger of sending the bias too far towards the person and in a way that I didn’t want in the equation at all. But when I added the two white rectangles, the name became useful in helping them read as the borders of a magazine page.

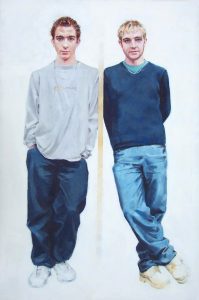

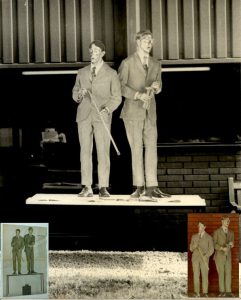

I was, by this time, an obsessive leafer through magazines of all kinds, on the look out for low level, long lens images of complete figures, and it was in one of these, a then three year old Sunday Times colour supplement that I discovered the image of the artists Gilbert and George.

B & W photograph of the cutout painting with colour insert (right)

and original magazine page (left)

It offered the perfect subject for another cut-out painting, Here were two artists presenting themselves in the gold painted flesh as a living work of art, and yet I could only experience them through a small, two dimensional image. What a hoot to take them part way back to the original by transforming that image into a life size cut-out. We even had the same style of table in the college refectory for them to stand on. Several weeks later and Gilbert and George were partially reborn and standing on a table liberated from Chorley College canteen.

Well, I thought it was hoot anyway.

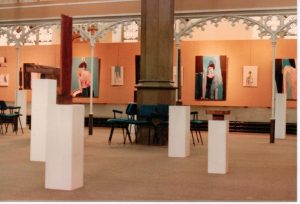

And then, before we all knew it the end of course show was upon us and I got to exhibit the work I’d done in the (new) college entrance hall.

This, amazingly it seems now, was the first time I’d had an exhibition. In fact, with exception of the Big Arrow piece in the college bar, which I’d never seen in situ anyway, I’d never exhibited any work at all – as an NDD student at art college I was assessed by exam not display. So being able to assemble the work I’d done over the last few years, work that I now felt confident about, was really quite wonderful.

And I got a top grade (A – there being no pluses or stars in those simpler days). I’d also got rid of the large F that art college had stamped on my forehead. I was an artist.

But I was an artist with a wife, two children, a mortgage, and no job.

Where next?

Back To Contents.

Chapter 4 – Vernon Gallery

Some fifteen years after the events described below I happened to take a nostalgic wander through my old slides. I don’t remember the reason, or even if there was one, just the unhappy discovery that one box contained mainly blanks. Some kind of microbe or chemical had eaten all the images leaving nothing but clear little windows. The main visual record of several years’ production was gone forever. The narrative which follows is therefore based on fragments of drawing, a few objects but too often unaided memory. The illustrations of it are, needless to say, also a bit thin.

“Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach,” said George Bernard Shaw in 1903. Lots of people at Chorley College were still saying it in 1975, usually adding …”and those who can’t teach, teach teachers.” I was inclined to go along with both versions but accepting the original left me in something of a dilemma. I’d just spent nine years proving, to my own satisfaction at least, that I could do. And since my one session of teaching practice in a secondary school hadn’t exactly inspired me with enthusiasm, I wasn’t sure I wanted to sew leather patches on the elbows of my jacket just yet (I didn’t have the right kind of jacket for one thing).

Yet what else was there?

There was no way I was going to break into the art world and make my fortune. Not from Chorley. And not with my personality. The attitude that had held me back so disastrously at art college – my deification of the teaching staff – still operated double with regard to the art world. And given my inability to interact with anyone I haven’t been introduced to (and, better still, imbibed alcohol with), even if I’d known where the art world lived I was psychologically incapable of approaching it. The only route to it that I could conceive of was via the art college system, by becoming a lecturer. But that was equally unattainable. I was under no illusions; even a top grade from a teacher training college carried about as much weight as a cycling proficiency badge to an art college.

So with some reluctance I consulted the pages of The Times Educational Supplement.

There were two Secondary School Art Jobs within travelling distance – both in Preston. The first, Ashton High School, wanted someone to teach Art for one year, the other, Tulketh High School, wanted an Art specialist to teach Art and something called Creative Design. So, as my wife and children looked on, their empty soup bowls clutched hopefully to their chests, I applied for both.

Of the two I wanted the Ashton job, because it was temporary. Another character flaw I suffer from is inertia – I was worried that once I got into a school I would never get out again (spot on there Stuart). At least with this job I would be forced out after a year, during which period I could have a good look at the alternatives. In addition, I had absolutely no idea what Creative Design consisted of. I got interviews for both, on consecutive days.

I didn’t get the Ashton job.

I arrived home afterwards feeling a bit miffed. Actually, I was bloody furious. Who did they think they were? I didn’t even want to be a teacher. They could stuff their so called profession. There was no way I was going to the Tulketh interview tomorrow. Sod ‘em.

But when I woke up the following morning, there were the little ones with their soup bowls again. Ah well, I decided, I might as well go and have a look. What harm could it do?

On such tiny pivots does life occasionally revolve.

I almost blew that interview too. In fact, had there been another candidate I almost certainly would have. But there wasn’t. Goodness knows why – perhaps nobody else knew what Creative Design was either, or maybe, more worryingly, they did.

But the headmaster and his Head of Art did decide to take a chance on the one bumbling idiot who had turned up and I was able to return home and inform the little ones that come September, their bowls would be full once more. We might even be able to afford bread to dip in the soup.

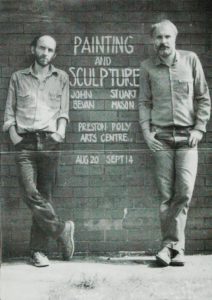

I was actually quite excited by the prospect of joining the Tulketh Art Department. It was staffed by two youngish males, both called John. McKay was head of department, Bevan his assistant. They both had a sense of humour and John B in particular was a committed, working artist. (John M, as far as I recall, preferred to go fishing).

Creative Design, I discovered, represented John M’s attempt at empire building – by expropriating some of the activities of Boy’s Handicraft into the Art Department. I was to be his fifth column in this endeavour, using the facilities of the Woodwork room to help first years make objects d’art instead of teapot stands, or at least better and more individually designed teapot stands. Needless to say, I wasn’t welcomed with open arms by Bill and Rod, the two traditionalists who worked there, particularly when they found out I had no woodworking skills to speak of. The saving grace was that the room was only free for a couple of the four or so lessons I was timetable to teach. I taught the rest in a small room near the Art Department. It wasn’t much bigger than an office (it was turned into one in later years) but it didn’t have Bill and Rod peeking into it from the stockroom so I preferred it.

As will be obvious from the above, my fifth column, Creative Design activities took up only a small part of my teaching timetable. So too, sadly, did Art. For the rest, well over half, I taught Technical Drawing – in the Dining Hall. This was another subject I knew nothing about. As so many teachers have done before me, I just stayed one week ahead in the textbook.

And whilst I spent my weekdays wrestling with the concepts of First Angle Projection, doing my best to placate Bill and Rod, juggling the cardboard boxes that were my mobile storeroom, and defending myself from the attempts of the pupil population to destroy me, in the evenings and at weekends I carried on being an artist.

I also began socialising with John Bevan.

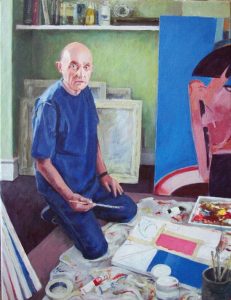

John and I got on well. We had, it turned out, a lot in common: we had both failed to take advantage of art college opportunities, both recovered ourselves through teacher training college and both felt defined by our continuing engagement with art. John, it must be said, was a very different artist from me. His artistic hero was Roger Hilton and his paintings reflected the fact.

Painting by John Bevan. Title unknown – his titles changed every time he exhibited them. Not sure about the colour either; it’s from an old slide.

I was still wandering about in the margins between drawing and painting, photography and three dimensional ‘reality’.

Without the space and facilities that Chorley College had offered the scale and scope of what I could produce was now much more limited. I did manage to create a makeshift darkroom in our little bathroom but there was no way I could overcome the lack of space. So life size, cut out paintings of figures, naked or otherwise, where out. I began to work on a much smaller scale.

Given the scarcity of visual reminders, it’s difficult to get the chronology right but what I am sure of is that the work followed two tracks: small cut out, free standing drawings of figures being one; an exploration of real objects, three dimensional drawings of those objects (explanation below), and areas in between, being the other.

A couple of the cut out figure drawings survived though not the structures they were displayed on.

Recently taken images of these figures give a flavour of how they worked. At the time I had slight reservations about the trickiness of some of them. This is exemplified by the leaning figure. My main concern, at the time, was that the tricksy, ‘gravity defying’ aspect of this image/object distracted from the important activity of exploring the interface between image and object, drawing and photograph. These days I like this tricksy element for its playfulness.

In the main, these cut out figures (there were, my imperfect recollection suggests, about half a dozen of them) were displayed on simple shelves with wooden backgrounds, though in at least one case the ‘shelf’ was angled downwards and wider at the front, giving it a false perspective. The figure in the one I remember was a bather emerging from the sea and the horizontal wood grain worked as the rippling water. I liked the way the actual texture connected with the image and took on the role of representing something other than itself.

In another variant the back board was a mirror. On the reverse of the cut out drawing I drew the image in reverse. Seen through the mirror this drawing was therefore the right way round. The spectator could thus see two images of the same figure: the cut out itself and a mirror image that wasn’t a mirror image behind it. I’ve been fascinated by mirrors on and off ever since.

As I have by grids. I had used graticulation, to use a posh term for it, to reproduce these and earlier photographic images and I now began to explore their potential. Spending as much time as I did looking through magazines in search of suitable images I became conscious of the various kinds of effects that different camera lenses produced. In the main I was searching for complete figures photographed with longish lenses but also encountered the opposite; wide angle images. Had I had enough money I might simply have bought a selection of these optical devices and gone out to experiment. Or maybe I wouldn’t; to be honest I enjoyed the challenge of creating a wide angle effect from an ordinary photograph using distorted squares. (I later became besotted with the humble grid distorted or otherwise. It came to dominate my artwork and my teaching. But I’m getting ahead of myself.).

At the same time (I think) I began to explore the 2D/3D, drawing/photograph/object interface from the opposite direction, by giving objects some of the qualities of images. It was largely still a black and white world back then. Although colour photography and reproductions had been around for a long time it remained expensive and most images, personal and public were in black and white. So simply making a piece of packaging ‘grayscale’ to use modern parlance (and spelling) was enough to move it closer to a two dimensional representation.

So I did, choosing, as subject, the then ubiquitous No. 6 cigarette packet, an example of which was never far from my elbow or pocket in those smoke filled days. I pulled open this familiar piece of packaging, flattened it out and reproduced it in pencil on clean white card. The result was then folded and glued to become a three dimensional drawing of sorts. I added a box of matches (with real matches painted grey) and set them on a piece of paper, on which was drawn a fake piece of paper visually held down with a pencil rendered drawing pin.

I then went on to make the Police Car piece, painting a model car grey and placing it on photograph taken from a suitable office block. This was the photograph to the No.6’s drawing.

John meanwhile, had gone and got himself an exhibition at a local gallery. This was the Vernon Galley, an attractive and prestigious exhibition space connected to and financed by a local graphics firm. When he applied for the exhibition it had been suggested that, even if he was accepted, it would be over a year before a slot became available, thus giving him time to build up a body of work. As it turned out they had a cancellation and offered him a slot only weeks away. Enter Stuart to help fill the space.

I’m not sure if John regretted asking the Vernon Gallery if I could share the exhibition, but I’m fairly sure that the Vernon Gallery regretted agreeing to it. But we’ll come to that in a minute.

In truth I’m not absolutely sure when exactly they did agree. Deeper reflection suggests it happened in the middle of the artistic production described above and acted as a driving force behind much of it, particularly the number of cut out figures. It certainly happened before the production of the HP bottle sequence. This turned out to be a major piece in my part of the exhibition since it took up a whole wall. It consisted of about eight HP bottles and images of same in various mixtures of representation and acuality. Annoyingly the only images which survive of this sequence are the really boring ones at the extremities of the sequence. The originalsequence, as far as I remember it, was: 1. empty bottle without label, 2 .empty bottle with outline label (Illustrated left), 3. drawn cut out, 4. bottle with fully drawn label filled with grey powder, 5. bottle with black and white photographed label filled with grey paint, 6. painted colour cut out, 7. bottle with painted label filled with brown paint, 8. unopened bottle of HP sauce. There could have been a cut out photograph in there too but I’m not sure.

The originalsequence, as far as I remember it, was: 1. empty bottle without label, 2 .empty bottle with outline label (Illustrated left), 3. drawn cut out, 4. bottle with fully drawn label filled with grey powder, 5. bottle with black and white photographed label filled with grey paint, 6. painted colour cut out, 7. bottle with painted label filled with brown paint, 8. unopened bottle of HP sauce. There could have been a cut out photograph in there too but I’m not sure.

I remember this piece causing a certain amount of consternation, of the “If that’s a work of art, I’m a Martian,” variety. But it wasn’t the exhibit that caused the real problem. That was Eve, the only piece not produced post Chorley College.

It never occurred to me that anyone would object to Eve. She had, after all, adorned the entrance hall of a College of Education a year or so earlier, a place where parties of schoolchildren had even been known to tread. But then Chorley College did have a bit if thing about being open minded. Not so, it turned out, the Vernon Gallery. The day after the private view they removed Eve along with a life sized drawing of a topless girl with her hand down the front of her trousers.

To be fair, I had put Eve in a provocative place. The gallery was adjacent to the works canteen and I had placed my life sized, cut out glamour girl, pubic hair and breasts resplendent, right next to the serving hatch.

Looking back I feel I took it well. In fact I saw what had happened as an affirmation of the piece. I explained this on the A4 typed sheet to which I attached a small black and white image of the missing art work.

I stuck this where Eve had been.

I stuck this where Eve had been.

There are those who would argue that I should have contacted the local evening paper and kicked up a stink. It never occurred to me at the time; I’m still not sure whether I’m proud or embarrassed by the fact that it didn’t.

I never did get Eve back. Someone did tell me that she graced the draughtsmen’s office for a while. How long a while I have no idea, but was happy she was there being ogled rather than stacked away unseen, warping and decaying, in my damp garage. What happened to her I have no idea. I assume she ended up in a skip though I suppose there is a miniscule chance that some retired architect still has her propped in the corner of his study. I can but dream.

Note. After reading the above, in his idyll in Spain where he now lives, John reminded me of the problems he too had experienced with that Vernon Gallery exhibition. He really had struggled to produce work for the exhibition since he was not only teaching during the day but working as a night-watchman into the early hours of each morning. He did, however, have lots of spare time during his late evening vigils. There wsn’t enough room to paint so he took to making small collages using coloured card. These beautiful little pieces – they were just slightly bigger than A4 – eventually took up a whole wall of the exhibition. Unfortunately, once up in the dry air of the gallery they started to spring into life. Whatever glue John had used proved to be unequal to the task; the cardboard shapes began to curl away from the surface. He spent the evening before the opening frantically gluing them back down again.

(He now claims it was “a bad batch of glue”.)

Below are some additional images. The images of the No.6 package, matchbox and car are modern photographs of the real objects. Both boxes are looking their age. Also exhibited is an image of Eve which has also suffered the effects of time (and whatever bug when through the other slides). I find myself thinking of the young woman depicted the original photograph and wondering what time has done to her.

Back To Contents.

Painting by John Bevan. Title unknown – his titles changed every time he exhibited them. Not sure about the colour either; it’s from an old slide.

The originalsequence, as far as I remember it, was: 1. empty bottle without label, 2 .empty bottle with outline label (Illustrated left), 3. drawn cut out, 4. bottle with fully drawn label filled with grey powder, 5. bottle with black and white photographed label filled with grey paint, 6. painted colour cut out, 7. bottle with painted label filled with brown paint, 8. unopened bottle of HP sauce. There could have been a cut out photograph in there too but I’m not sure.

The originalsequence, as far as I remember it, was: 1. empty bottle without label, 2 .empty bottle with outline label (Illustrated left), 3. drawn cut out, 4. bottle with fully drawn label filled with grey powder, 5. bottle with black and white photographed label filled with grey paint, 6. painted colour cut out, 7. bottle with painted label filled with brown paint, 8. unopened bottle of HP sauce. There could have been a cut out photograph in there too but I’m not sure. I stuck this where Eve had been.

I stuck this where Eve had been.Back To Contents.

“Being ‘discovered’ is the dream of many painters and sculptors. Well, for two Preston based artists the dream is about to come true. Stuart Mason and John Bevan have created something of a stir with their recent exhibition at the Vernon Gallery in Preston, so much so that there is talk of the exhibition being moved to one of the more prestigious London galleries...”

Alas no. That isn’t quite what happened. If anyone with influence, a media voice or just someone with an inclination to flatter, did see our exhibition they chose not to mention the fact. When the show came to an end we just collected our work (less Eve) and scurried back to our semis in Penwortham (where we both now lived). John carried on painting and I carried on mucking about with photographic imagery. The pace of my production slowed down however.

John had by this time left Tulketh to become Head of Art at Lostock Hall High School where he would eventually see out his career. One consequence of this was that I now had a lot more Art on my timetable. Teaching Art didn’t yet take on the importance in my creative life that it would later do, but it was sufficiently interesting and challenging to suck up some of my creative juices. Add that to the deflating effects of the Vernon Gallery exhibition and periods of inactivity began to creep into my personal artistic journey. I certainly didn’t stop altogether but what work I did tended towards the experimental – just mucking about with photographs and drawings might be a more down to earth way of putting it – but I never really reached the kind of definitive conclusions that my earlier work had done.

I was, quite simply, running out of steam.

And then came the summer of 1981, one of the few moments I can put an actual date to with some degree of certainty. My artistic production ceased altogether. It was a temporary interruption lasting about a year. In short, I took up writing.

I had always written a little – the staff pantomime, humorous reports on staff cricket matches – but nothing serious. That summer, bored and a little disillusioned with making artwork, I embarked on a novel. I bought myself a small portable typewriter and wrote for much of the summer holidays. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing and this, strangely enough, was what I liked about it. I had no history as a writer (apart from the scraps mentioned above), no standards to live up to and nothing to prove. I could just enjoy myself. And I did.

At the end of the six week break I went back to school and the rate of production slowed. It would probably have stopped altogether, never to start up again, if it hadn’t been for a couple of colleagues, one a poetry writing Head of English, the other a Geography teacher with a tendency to quote Shakespeare. I announced to these two buddies one night over a pint that I had embarked on a novel. Neither of them said anything – which was bad enough – but their gazes seemed to wander slightly as if in search of flying pigs. Then they changed the subject. I went away that night a determined man.

It was no small effort and took the rest of year. I wrote in long hand, in pencil, with much rubbing out and alteration. I even physically cut and pasted (well, sellotaped). And then I laboriously typed each chapter up on the portable. The result was a comic novel called ‘Witters’.

Looking back, it’s a flawed book. I was learning as I went along and in the early chapters it shows. Not the first chapter – I rewrote that every time it came back from the publisher with a rejection slip – so that’s not bad. But the few following that are a bit pedestrian. It gets better once it gets going; it’s positively hilarious in places and has an exciting ending.

At the time I only had two copies, the original and a poor quality photocopy. So the relatively good one went off to one publisher at a time, carrying all my hopes and dreams with it, the latter only to be dashed when it came back two months later. But somehow the hope would fill up again, like the energy level in a shoot ‘em up video game, and I’d parcel it up and send it to the next one (after rewriting the first chapter).

In the meantime I went back to Art.

Not that I abandoned writing for good. The dream of getting published may have faded but the pleasure I got from the process of writing itself remained; particularly from writing a novel. During the year that it took me to write a book length work of fiction I had two lives running side by side: a real life and a fictional one. And in the fictional one I got to play god.

So in amongst the work described in the following chapters I continued to write, on and off. Three more novels followed over the years. I loved writing them. the middle two are on Kindle. I neither recommend nor renounce them. They’re just there; the digitised remnants of a few years of marvellous distraction.

Below are images of the four books. I unpublished ‘Witters’ , ‘Drawn In’ has yet to be published.

The artwork I produced following that hiatus was very different from the stuff which preceded it. It was more intuitive, more abstract and completely medium driven.

The medium was wood, specifically driftwood collected from the River Ribble, the banks of which I used to walk along whilst waiting for my novel to find a publisher.

Mention driftwood, in an artistic context, and listeners are wont to imagine the exotic natural forms of tree branches and roots, worn grain-revealingly smooth by the actions of the tides, and needing only the merest tweak to turn them into a cute little squirrel or a rampant stallion. It is true that I had used such bits of aesthetically pleasing bric-a-brac in my early teaching (much to the horror of the woodwork teachers whose workshop I was teaching in and with whose precision tools my first year pupils were happily sawing and hacking away at the lumps of half dried out detritus I’d given them). No, the stuff I was personally drawn to was more man-made industrial than nature’s bounty: blocks, wedges and planks to be exact, stuff that had fallen off the decks of passing cargo ships. Preston, in those days, still had a working dock, albeit a dying one and merchant ships still occasionally chugged up and down the river, losing, or discarding, a surprising amount of their contents in the process.

It was the wedges that attracted me first. These were six or seven inch long, triangular sections of wood and littered the river bank along its length. They had obviously been used to stabilise cargo on the decks and in the holds of the ships and boats. They were of uniform size but varied in their colour, grain patterns and condition. I began to collect them. And back at home, in the back garden of our little semi, I contemplated turning them into some kind of sculpture.